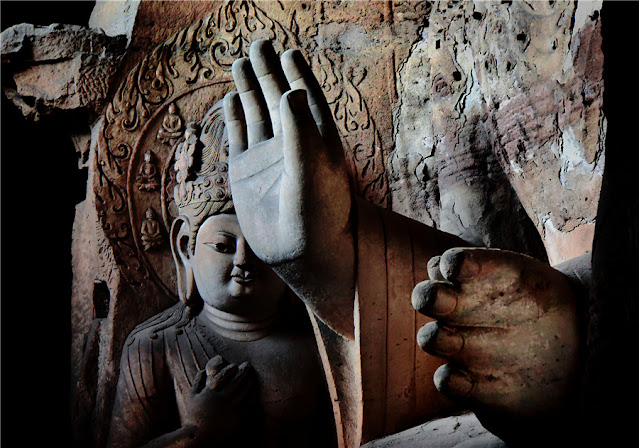

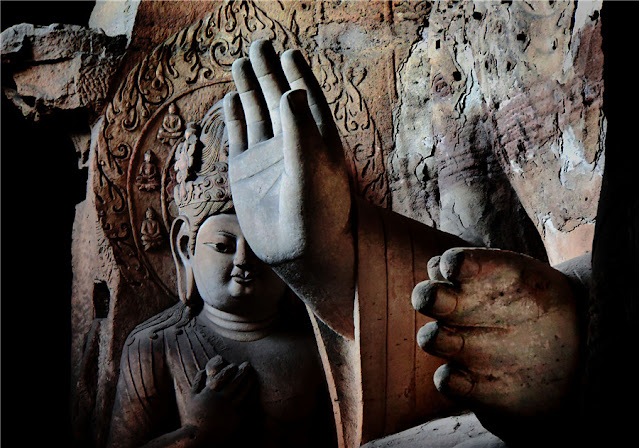

|

| Vardhman Mahavira |

Jesus Christ was born in 6 BCE (before common era). His religious teachings heralded a socio-religious revolution in the West. He preached peace to an extremely quarrelsome population from the deserts of Arab to the greeneries of Greece and Italy. But historians tell us that the real impact of the Christ revolution happened after Jesus Christ's teachings hit the head of Constantine One or Constantine, the Great.

Though some historians doubt his absolute belief in Christianity but they agree that he identified himself as a Christian. One particular incident is often cited. That when he was leading his army to fight off an invader, a pagan, just outside Rome in the early fourth century (311-12), he saw an image in the sky. As the narrative goes, his enemy believed in a prophesy that the enemies of Rome would prevail in the war. Constantine, on the other hand, saw an image in the sky -- Chi-Ro (kee-ro), represented by two Greek letters -- x and p -- combined together with words inscribed on air: by this sign, conquer.

He led his army to victory. The next year, he declared persecution of Christians illegal in Rome. He made Chi-Ro the official insignia of his army, which won many a battle, vastly expanding the Roman empire, and made Byzantine his capital christened as Constantinople, now Istanbul. This Chi-Ro later became the Christian Cross for the Christian armies. The impact of his deeds was such that Christianity was declared the official religion of Rome seventy years later.

This story is originally very long. I have tried to tell it in short. Even this abridged version is lengthy for a write-up on how socio-religious movements happened in India many a centuries before Christianity made a true impact in the West. But I told this story on purpose. Most people need a reference point or a familiar background against which they appreciate some intrinsically known facts. We tend to get used to the worst and the best almost in the same mental-psychological manner. We just get used to it.

I had read somewhere that when Mahavira and Buddha happened to the Indian subcontinent, there were more than 560 (562, if I remember correctly) socio-religious reformers of repute. This was happening more than 500 years before Christ was born, and more than 800 years before Christianity began taking its real shape. And unlike Christianity, the most popular religion on the planet, none of these socio-religious philosophies needed an army to stamp their authority on the minds of the then-Indian population. All of them received respect from people even though many of them fought among themselves in their bid to establish superiority of their own philosophy.

So, the natural question is, why India produced so many reformers and two of the world's greatest ever in those years?

Society must have needed them. There must have been situations or a culmination of situations which saw society producing these luminaries and accepting them as the guiding lights. The answer to this question could be found in existing social-religious conditions and the material progress of the time. Let's reconstruct both these aspects here.

Social background

In the earlier times, Vedas and Upanishads were the core of socio-religious beliefs. The language of these literature was Sanskrit, a chaste form compared to modern-day Sanskrit to the extent that many historians prefer to call it Vedic Sanskrit or archaic Sanskrit. The population generally spoke their regional languages with enough number of people knowing a few languages from different parts of India. I am not sure when it happened a disconnect had been established between what was written in the Vedas and Upanishads, and what reached to the common people not versed in Sanskrit.

This disconnect had a strong link to how society stratified over the past one thousand years or so. By now, society was clearly divided into four varnas: Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras. It is remarkable to note here is that Brahmanas were originally one of perhaps 16 classes of Vedic priests. But by sixth century before common era, they had developed into a separate caste with their own sub-castes with a claim to the top stratum of society. But their claim was not yet unchallenged. Kshatriyas, who practically owned geography-clamped societies, jostled for supremacy, some of the historians tell us.

|

| Monolithic statue of Gautam Buddha installed in a Hyderabad lake (Pic: Twitter) |

Vish of the Rig Vedic times had classified themselves in several castes but maintained their Varna identity. Shudras had developed from all other Varnas but now had a relegated position for engaging in labour-intensive activities. It is ironical to see that both Kshatriyas and Shudras were in labour-intensive fields, and performed two equally significant basic functions of a society but were seen differently, and occupied almost the extreme ends of the social ladder. Kshatriyas provided protection to society. Shudra fed society, clothed it, gave it shoes, manufactured weapons of protection and served the rest in every possible way to ensure that societal communities continue to flourish.

Now, each Varna was assigned well-defined functions. But unlike the Vedic times, the Varnas were now emphatically based on birth. The two top Varnas enjoyed some privileges. Brahmanas were considered the storekeeper of knowledge and wisdom. This gave them intellectual and psychological superiority over the rest. However, it seems illogical that all from the Brahmana Varna enjoyed the same authority over the rest. There must have been poor among them who had to toil hard to eke their livelihood. But they could not contribute to literature. So, their status is completely unknown. We anyway know only what has survived. The rest is an informed logical guess.

Brahmanas were priests and teachers. They demanded several privileges including those of receiving gifts from the kings, local chieftains and the common people, and also exemption from paying taxes and subjection to punishments for various crimes, if and when they committed. However, they must not have been getting a blanket cover from punishment or were offered gifts without questions or with total devotion as the fate of Chanakya is well-documented.

He lived some 300 years after this phase of socio-religious reforms. Still, he could not claim all that authority which literature of the past generally makes us believe. Again, we know only what has survived. Chanakya was poor despite his father being a well-reputed scholar. He goes to the emperor but was not given gifts that he wanted. He was, in fact, ridiculed. He ended up insulting the king in a fit of rage, and in return, got banished. So, Chanakya originally got neither gift nor exemption from punishment. But some must have got both. This can be compared with today's societal set-up. Not all politicians or professors are equally prestigious or powerful.

Kshatriyas fought and governed claiming taxes, and living off the revenues collected. They were the real power-wielders. But again not all Kshatriyas could have been equally powerful. Obviously, one could be the king and the other the front-line foot-soldier.

|

| (Photo: Twitter) |

The Vaishyas engaged in agriculture, cattle rearing and trade. They employed Shudras in big numbers for their activities. They appear as the principal tax payers. However, along with the two other higher Varnas, they were placed in the class of Dwija -- or twice-born people. This meant that they could hold the investiture ceremony, in which an adolescent male could wear a ceremonial thread across his torso. The three Varnas had different rules for wearing the sacred thread.

Shudras were not allowed to organise the investiture ceremony for themselves. They were supposed to serve the other three Varnas. They along with women of all Varnas were practically denied Vedic education or studies. However, again the literature from later years -- the Chanakya-Chandragupta years -- indicate that this rule must not have been strictly followed or enforced by the ruler-teacher class. For, we see the Nanda dynasty emerge as the most powerful ruling family before the Mauryas came on the scene. The Nandas were said to be from the Shudra Varna. And the Mauryan literature talks about powerful women. The emperor himself was protected by a band of women bodyguards. This would not have been possible if society was so dead against Shudras and women as the surviving literature from the socio-religious upheaval years makes us believe.

But yes, Shudras and women were by now employed as domestic help and lived like slaves. Slaves in India were not comparable to the slaves recorded in the West. Here, their living condition was much more humane making a fourth century Greek ambassador believe and record that India did not practise slavery. Maybe, the Sanskrit word "dasa" is not the correct parallel of "slave" of English.

Shudras were the chief manual labour force in the agricultural field -- some were agricultural slaves. They were craftsmen and craftswomen. They were practically hired for every vocation or business that needed manual labour except warfare. They might have been employed there in support staff as baggage and weapon carriers. Some literature, as historians say, describe them as cruel, greedy and thieving in habit, and some of them were treated as untouchables. Shudras must have made up the biggest chunk of society, and must have felt utterly frustrated with their social, economic and religious positioning in that societal set-up just because of their birth to a particular couple branded as belonging to a particular Varna.

There must have been yearning for luxury and respect among them. The societal set-up was such that the higher the Varna the more privileges and purity one could claim. For the same offence, Shudras would get severer punishment compared to Brahmanas.

Naturally, Varna-divided society would have generated tensions. There are no means to ascertain the reactions from Vaishyas and Shudras. But Kshatriyas, who were the royalty, recorded their reaction against the ritualistic domination of Brahmanas. They appear to have led a sort of protest movement to demolish the principle of importance attached to birth in the Varna system. Their protest saw Brahmanas as targets, not violent but ideological. It is no mere coincidence that the two of the greatest socio-religious leaders were Kshatriyas -- Vardhman and Gautam.

Material base

This is considered as a bigger factor contributing to the rise of socio-religious reforms in the sixth century before common era. It was the time of the introduction of a new agricultural economy in the middle and lower Gangetic plains. Introduction of iron technology to agriculture heralded the transformation.

These areas -- from Bihar-Bengal to eastern Uttar Pradesh -- were thickly forested in earlier times. The Aryan people cleared the forests for agriculture, as literature suggests. In the middle Gangetic plains, large scale habitations emerged around 600 BCE, as a result. The use of iron implements made forest clearing, farming and large-scale settlements easier. Agriculture-based economy got a new fillip with iron ploughshare, which required the use of bullocks. The supply of bullocks needed a flourishing animal husbandry as vocation.

|

| It was not that only Magadh rose to power. Kingh Kharvel invaded Magadh and defeated its king, and brought back Jain's statue to Kalinga (Photo: Twitter) |

A whole new economic equation came into place. This was in a sharp contrast to the Vedic practice of indiscriminate sacrificing of cattle -- a necessity of the time to maintain a population balance in a society that thrived on milk and other cattle products, and used the same for transportation. The sacrifice of cattle in religious ceremonies meant that demand for bullocks could not be met. This came in the way of the new phase of agricultural revolution. The cattle wealth had slowly declined, the historians tell us. They also tell us that some communities, particularly those living on the southern fringes of the emerging Magadh empire, killed cattle for food. New agricultural revolution challenged their food habit by making availability of food easier than before, and also needed them to change their food habits so that there was no short-supply of cattle needed for the farms.

If the new agrarian economy had to be stable, this indiscriminate killing of cattle with religious sanction needed to be stopped. A new guiding religious belief had to emerge to sustain the civil living based on new agricultural revolution.

In other words, the time had come for an idea backed by socio-religious philosophy that could preach absolute non-violence in an intellectually and spiritually glamourised fashion.

The period saw the rise of a large number of cities in the middle Gangetic plains. We all know a city organically grows only when there is abundant supply of food. If food supply is not assured, hunting, gathering or farming remains the primary vocation. City-life is a tertiary scale of socio-economy. These new cities needed and had many artisans and traders, who began to use coins for the first time on regular basis for economic exchange. The earlier barter economy exchange model could not support the growth. The earliest coins to survive belong to the fifth century before common era, and are called the punch-marked coins.

The use of coins naturally facilitated trade and commerce, which added to the importance of Vaishyas. But in the Brahmanical order, they did not get much importance. So, they looked for an order, which would improve their social position. This is why Vaishyas extended generous support to both Mahavira and Buddha.

Further, Jainism and Buddhism, in their initial stages, did not attach any importance to the existing Varna system. Secondly, they preached the gospel of non-violence, which would put an end to wars between different kingdoms and consequently promote trade and commerce. Third, the Brahmanical law books, called Dharmashastras, decried lending money on interest. A person who lived on interest was condemned by them. Therefore, Vaishyas were not held in esteem and were eager to improve their social status.

On the other hand, there was a also strong reaction against various forms of private property. The new forms of property created social inequalities, and caused misery and suffering to the masses. So, the common people yearned for a more harmonious life and society. The ascetic ideal was one of the ideas espoused by the Vedas. A section of society now must have wanted to adopt this ideal, which was dispensed with the new forms of property and the new style of life.

Both Jainism and Buddhism preferred simple puritan ascetic living. The Jain and Buddhist monks were asked to forego the good things of life. They were not allowed to touch gold and silver. They were to accept only as much from their patrons as was sufficient to keep their body and psyche in harmony. The people, therefore, identified themselves such monks and supported the religious reactions against the Vedic religious practices.

Also, since both Vardhman and Gautam came from ruling Kshatriya families, they commanded authority over both the priestly class and the common populace. Their ideas were patiently listened to, and adopted as far as possible. Since they came from Kshatriya Varna, the Brahmanas could not denounce them with arguments that they were not versed in the Vedas. This logic would not have any weight in society. Brahmanas were the interpreters of the Vedic religion and system, and Kshatriyas were enforcer of the order.

Now, Kshatriyas took up the task to modify the social order and bring about a socio-religious reform. This went a long way in giving Jainism and Buddhism credibility as the royal warrior class produced teachers who preached peace and denounced the malpractices of the Vedas. This explains why unlike Christianity, where a non-violent preacher Christ needed a warring emperor to take off 300 years later, Jainism and Buddhism got royal support almost since their beginning, and none used the new religious ideas to launch a war on the other kingdom. Both kingdoms could be adopting the new ideas. And it also explains why Mauryan emperor Ashoka took the task of spreading Buddhism after renouncing warfare.