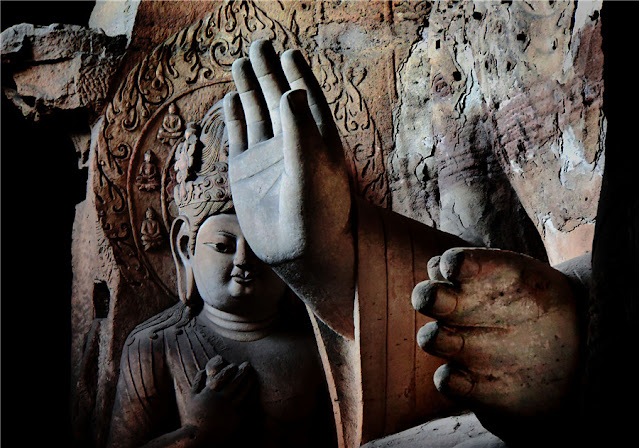

Maurya emperor Ashoka riding a chariot in a Sanchi Stupa relief (Photo: Twitter)

Ashokan

policy of Dhamma has been a topic of lively discussion and the best source to

know about his Dhamma is his edicts. The edicts were primarily written to

explain to the people the principles of Dhamma. What comes out from his edicts

is that the Dhamma was not any particular religious faith or practice. It was

also not an arbitrarily formulated royal policy. Dhamma related to the norms of

social behaviour and activities in a very general sense and in his Dhamma,

Ashoka attempted a very careful synthesis of various norms which were current

in his times.

The Dhamma

had a historical background that served as a set of causes effecting in an

official policy of one of the most powerful kings the world has seen.

SOCIOECONOMIC BACKGROUND

The Mauryan

period witnessed a change in the economic structure of society largely due to

the increasing use of iron. It has generally been argued that the use of the

Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) pottery is an indicator of material

prosperity of the period.

The use of

punch-marked coins of silver and some other varieties of coins, the conscious

intervention of the state to safeguard trade routes and the rise of urban

centres point to a structured change in the economy. It required necessary

adjustments in society.

The

commercial classes had also come to the forefront. The emergence of urban

culture by its very logic demanded a more flexible social organisation.

The

incorporation of tribes and peoples from the outlying areas into the social

fabric also presented a problem. The rigidity of the Brahmanical class

sharpened the division within society. The lower orders turned to various

heterodox sects and this created social tensions.

It was this

socioeconomic situation which emperor Ashoka inherited when he ascended the

Mauryan throne.

RELIGIOUS BACKGROUND

The

Brahmanical hold over society was increasingly coming under severe attack. The

privileges of the priests, the rigidity of the caste system and elaborate

rituals were being questioned. The lower orders among the four caste-classes

began to favour new sects. The opposition to the Brahmanism by the commercial

class was to give a fillip to the other sects of society.

On the

other hand, Buddhism opposed the dominance of the Brahmanas and the concept of

sacrifice and rituals. Buddhism had begun as a schismatic movement from the

more orthodox Brahmanism. Its fundamentals were based on an emphasis on misery

and advocacy of the middle path. It appealed to the lower orders and to the

emerging social classes. The humane approach to relations in society preached

by Buddhism further attracted different sections to Buddhism. Ashoka’s Dhamma

bore deep influence of Buddhism.

POLITICAL BACKGROUND

By the time

Ashoka ascended the throne, the state system of Mahajanapadas had grown very

elaborate and complex from where it had started during the Mahajanapada era.

Now, there

was political supremacy of one region (Magadha) over a vast territory which

comprised many previous kingdoms, gana-sanghas and areas where no organised

states had existed before.

Within this

vast territory, there was existence of various geographical regions, cultural

areas and different beliefs, faiths and practices.

There was

monopoly of fore by a ruling class of which the emperor was the supreme head.

The state

appropriated a very substantial quantity of surplus from agriculture, commerce

and other sources.

A large

administrative apparatus was developed for governing the people and

territories.

The

complexity of the state system demanded an imaginative policy from the emperor

based on minimal use of force in such a large empire having diverse forms of

economy and religions. It could not have been controlled by an army alone. A

more feasible alternative was the propagation of a policy that would work at an

ideological level and reach out to all sections of society.

The policy

of Dhamma was such an endeavour. Obviously, the policy of Dhamma was an earnest

attempt at solving some of the problems a complex society faced. However, it is

also true that Ashoka’s personal beliefs and his own perception of how he

should respond to the problems of his empire were responsible for the

formulation of the policy of Dhamma.

CONTENTS OF DHAMMA

The

principles of Dhamma were so formulated as to be acceptable to people belonging

to different communities and following any religious sect. Dhamma was not given

any formal definition or structure. It emphasised on toleration and general

behaviour of people. Its emphasis in particular was on dual toleration – of

people themselves and also their various beliefs and ideas.

There is

stress on showing consideration towards slaves and servants, obedience to

elders, and generosity towards the needy, Brahmanas and Shramanas. Ashoka prescribed

tolerance of different religious sects in an attempt to create a sense of

harmony.

The policy

of Dhamma also laid emphasis on non-violence, which was to be pracised by

giving up war and conquests, and also as a restraint on killing of animals.

However, Ashoka was conscious that display of his political and military might

up to a certain degree could be necessary to keep his empire intact and certain

sections of people, especially some primitive forest tribes in check.

The policy

of Dhamma included certain welfare measures such as planting of trees, digging

up of wells etc. Ashoka denounced certain ceremonies and sacrifices practised

regularly on various occasions as meaningless.

A group of

officers known as the Dhamma Mahamattas were instituted to implement and

publicise various aspects of Dhamma. Ashoka thrust a very special

responsibility on them to carry his messages to various sections of society.

However, they seem to have developed into a type of priesthood of Dhamma with

great powers and soon began to interfere in politics as well.

DHAMMA AS PER MAJOR ROCK EDICTS

Major Rock Edict-I

It declared prohibition of animal

sacrifice and holiday festive gatherings.

Major Rock Edict-II

It related to certain measures of social

welfare which were included in the working of Dhamma. It mentioned medical

treatment for men and animals, construction of roads, wells and planting of

fruit-bearing trees and medicinal herbs.

Also talked about states outside the

boundaries of Magadh empire: Pandyas, Satyapuras and Keralaputras of South

India.

Major Rock Edict-III

It declared that liberality towards

Brahmanans and Shramanas is a virtue. Respect to mother and father is a good

quality to have. Empire officials Yuktas, Pradeshikas and Rajukas would go

every five years to different parts of his empire to spread Dhamma.

Major Rock Edict-IV

Dhammaghosha (bugle of righteousness or

Dhamma) over Bherighosha (bugle of war). It said that due to the policy of

Dghamma, the lack of morality and disrespect towards Brahmanas and Shramanas,

violence, unseemly behavior towards friends, relatives and others, and evils of

this kind have been checked. The killing of animals to a large extent was also

stopped.

Major Rock Edict-V

It referred to the appointment of Dhamma

Mahamattas for the first time in the twelfth year of his reign. These special

officers were by the emperor to look after the interests of all sects and

religions and spread the message of Dhamma in each nook and cranny of the

state. The implementation of the plicy of Dhamma was entrusted in their hands.

It talked about treating slaves right

and humane.

Major Rock Edict-VI

It was an instruction to Dhamma

Mahamattas. They were told that they could bring their reports to the emperor

at any time, irrespective of whatever activity he may be engaged in. the second

part of the edict dealt with speedy administration and smooth transaction of

business.

Major Rock Edict-VII

It talked the necessity of tolerance

towards different religions among all sects, and welfare measures being

undertaken by the emperor/empire for the public not only within the Magadhan

territories but in his neighbouring kingdoms as well.

Major Rock Edict-VIII

It talked about Dhammayatras saying that

the emperor would undertake these tours instead of traditional hunting

expedition to improve and deepen his contact with various sections of people of

the empire.

It mentioned about Ashoka’s first visit

to Bodh Gaya and Bodhi Tree, giving importance to Dhamma Yatra.

Major Rock Edict-IX

It attacked ceremonies performed at

birth, illness, marriage and before setting out for a journey. A censure was

passed against ceremonies observed by wives and mothers. Ashoka instead laid

stress on the practice of Dhamma and usefulness of ceremonies.

Major Rock Edict-X

It denounced fame and glory, and

reasserted the merit of following the policy of Dhamma.

Major Rock Edict-XI

It is a further explanation of Dhamma

with emphasis on showing respect to elders, abstaining from killing animals,

liberality towards friends and being humane towards slaves and servants.

Major Rock Edict-XII

Similar to MRE-VIII, it reflected the

anxiety of Emperor Ashoka that he fled owing to conflict between competing sects

and carried instructions for maintaining harmony.

It mentioned about Ithijika Mahamatta,

the high-ranking official in charge of women’s welfare.

Major Rock Edict-XIII

It is of paramount importance in

understanding the Ashokan policy of Dhamma. It prescribed conquests by Dhamma

instead of war. This was a logical culmination of the thought process which

began with the first MRE. This is Ashoka’s testament against war. It

graphically depicted the tragedy of war.

This MRE was issued at the end of the Kalinga

War bearing testimony to how Ashoka underwent a change in heart from an being aggressive

and violent warrior to a preacher of peace and Dhamma.

It gave details of Magadha’s victory

over Kalinga and mentioned Ashoka’s Dhamma Vijay over Greek kings Antiochus of

Syria (Amtiyoko), Ptolemy of Egypt (Turamaye), Magas of Cyrene (Maka),

Antigonus of Macedon (Amtikini), Alexander of Epirus (Alikasudaro). It also

mentioned about Pandyas and Cholas in South India.

There is another MRE, the fourteenth. It

entailed the purpose of rock edicts – to spread Dhamma and policies of the

emperor.

PS: Ashoka put out his instructions

through a series of edicts inscribed on rocks installed across his empire.

These edicts are categorized by historians into five simpler groups:

-

Major Rock Edicts

-

Minor Rock Edicts

-

Separate Rock Edicts

-

Major Pillar Edicts

-

Minor Pillar Edicts

There are altogether 33 inscriptions

that have been found in the edicts recovered/survived so far.

ASHOKA’S DHAMMA AND HIS STATE

Ashoka’s

Dhamma was not simply a collection of lofty and feel-good phrases. He

consciously adopted Dhamma as a matter of state policy.

It was a

major departure from Arthashastra, the political treatise that formed the basis

of kingship during Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the dynasty. In the

Arthashastra, the king owed nothing to anyone. His only job was to rule the

state efficiently.

But

Ashoka’s Dhamma was a state policy. He declared that “all men are my children”

and “whatever exertion I make, I strive only to discharge the debt that I owe

to all living creatures”. It was totally a new and inspiring ideal of kingship.

Ashoka

wanted to conquer the world through love and faith and hence he sent many

missions to propagate Dhamma to even far flung places such as Egypt and Greece

besides relatively nearby Sri Lanka.

The

preparation of Dhamma included several measures for people’s welfare. Centres for

medical treatment of men and animals/beasts were founded inside and outside the

empire. Shady groves, wells fruit orchards and rest houses were laid out. This

kind of charity work was a radically different attitude from the king of

Arthashastra, who would not incur any expenses unless they brought more

revenues in return.

Ashoka

prohibited useless sacrifices and certain forms of gatherings which led to

waste, and indiscipline and superstition. He recruited Dhamma Mahamattas for

that purpose. They were to see to it that people of different sects were

treated equally and fairly. Moreover, they were also asked to look after the

welfare of prisoners. Many of the convicts who were kept in fetters after their

sentence had expired were to be released. Those sentenced to death were to be

given a grace for three days.

Ashoka

launched Dhamma Yatra, righteous tours. He and his high-ranking officials were

to tour the country in order to propagate Dhamma and establish direct contact

with his subjects.

Ashoka

renounced war and conquest by violence, and forbade killing of many animals.

Ashoka himself set an example of vegetarianism by almost stopping consumption

of meat in his royal household.

It was

because of such attitudes and policies that modern writers like Kem called him

“monk in a king’s garb”.

DHAMMA: INTERPRETATION

It has been

suggested that it was the original Buddhist thought that was being preached by

Ashoka as Dhamma, and later on, certain theological additions were made to

Buddhism. This kind of thinking is based on Buddhist chronicles. But

definitely, Ashoka did not favour Buddhism at the expense of other religious

beliefs.

Ashoka’s

creation of the institution of Dhamma Mahamatta indicates that Ashoka’s Dhamma

was not to favour any particular religious doctrine. Had that been the case,

there would not have been any need for such an official as Ashoka could have

utilised the organisation of Sangha to propagate Dhamma.

Further,

Ashoka wanted to promote tolerance and respect for all religious sects, and

duty of the Dhamma Mahamattas included working for Brahmanas and Shramanas.

Some

historians have suggested that Ashoka’s banning of sacrifices and the favour

that he showed to Buddhists led to Brahmanical reaction, which, in turn, led to

the decline of the Mauryan empire. Others believe that the stopping of wars and

emphasis on non-violence crippled the military might of the empire. This led to

the collapse of the empire, after the death of Ashoka.

However,

Romila Thapar has shown that Ashoka’s Dhamma, apart from being a document of

his humanness, was also an answer to the socio-political needs of the

contemporary situation.

That it was

not anti-Brahmanical is proven by the fact that respect for Brahmanas and

Shramanas was an integral part of Ashoka’s Dhamma. His emphasis on non-violence

did not blind him to the needs of the state. He warned the Atavikas (forest

tribes) of using the military force of the empire if they did not mend their

ways.

Ashoka’s

‘no to war’ policy came at a time when his empire had almost reached its

natural boundaries. In the deep south, he had friendly ties with the Cholas and

the Pandyas. Sri Lanka was an admiring ally. The policy of tolerance was a wise

course of action in an ethnically diverse, religiously varied and class-divided

society.

Ashoka’s

empire was a conglomerate of diverse groups. There were farmers, pastoral

nomads and hunter gatherers besides a burgeoning urban population. There were

Greeks, Kamobjas and Bhojas, and hundreds of groups following divergent

traditions.

In such a

society and political composition, the policy of tolerance was the need of the

hour. Ashoka tried to transcend the parochial cultural traditions by a broad

set of ethical principles. It is, therefore, obvious that he was not

establishing a new religion. He was simply trying to impress upon his society

to guide along ethical and moral principles that suited his politics quite

well.