|

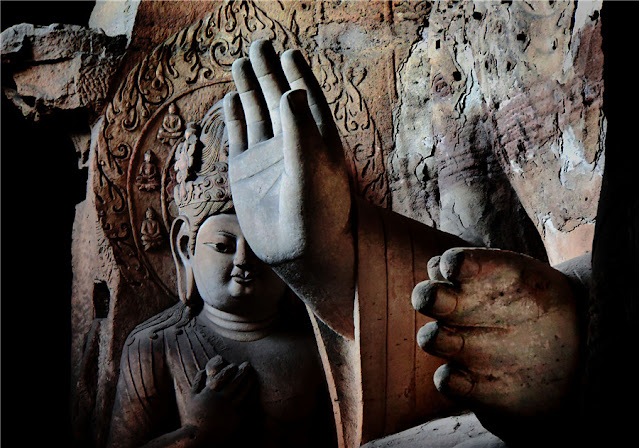

| Remains at Kapilvastu: Brick structure dating back to 6th century BC at Ganwaria near Piprahwa, Balrampur, UP. Twenty-five rooms were found during excavation leading to identification of the lost city of Kapilvastu, the capital of King Shuddhodhan, the father of Mahatma Buddha. (Photo: Twitter/Indianhistorypics) |

This period

is also known as the era of Mahajanapadas. There were 16. This is also the

phase of socio-religious movements that saw emergence or consolidation of

Jainism, Buddhism, Bhagavat belief system and Brahmanism.

Buddhist

text Anguttara Nikaya provides details of the 16 Mahajanapadas, also in Pali

literature. Another text Janavasabhasutta talks about 12 Mahajanapadas while

Chullaniddesha has a slightly different list of Mahajanapadas. It counts 17 by

adding Kalinga to the list and replacing Gandhara by Yona. Mahavastu’s list is

also a little modified with Shivi and Dasharna coming in place of Gandhara and

Kamboja.

The

commonly held 16 Mahajanapadas were:

1. Kashi in Varanasi

2. Koshal in Ayodhya-Shravasti region

or the Awadh region

3. Anga in East Bihar around Champa,

Bhagalpur-Munger

4. Magadha in South Bihar around

Girivraj, Rajgriha

5. Vajji in North Bihar, around

Vaishali, a congregation of tribes

6. Malla in Pava in East UP, around

Gorakhpur-Deoria, a congregation of tribes

7. Chedi, in Bundelkhand region

8. Vatsa in Kaushambi, near

Allahabad/Prayagraj in UP

9. Kuru in Indraprastha, in

Delhi-Haryana region

10. Panchal in Kampilya, around

Ruhelkhand region

11. Matsya in Viratnagar in Rajasthan

12. Shurasena in Mathura, in West UP

and around Delhi

13. Asmaka or Asika, in Potana or

Paithan in the source region of the Narmada

14. Avanti in Ujjaini and Mahishmati in

Malwa region, Central India

15. Gandhara in Takshashila, NW

Pakistan

16. Kamboja in Rajpur, west of Gandhara

Jain text

Bhagavatisuttra provides the list with slightly different names for some of the

Mahajanapadas. They are:

1. Kashi

2. Koshal

3. Anga

4. Vajji

5. Magadh

6. Banga

7. Malaya

8. Malaw

9. Achchha

10. Vachchha

11. Kochchha

12. Padhya or Pundra

13. Ladha or Radh

14. Moli

15. Awadha

16. Sambhuttara

The

Bhagavatisuttra mentions new Mahajanapadas not mentioned in Buddhist Anguttara

Nikaya, such as Banga and Radh. The geographical location of Sambhuttara

Mahajanapada is not clearly known. It is speculated that it might have been

somewhere in the northwest region of ancient India. Achchha and Vachchha

Mahajanapadas might have been located in Gujarat. Pundra was possibly located

near Banga.

It is clear

that two literary sources give two different sets of 16 Mahajanapadas. Some of

the names are different. Historians have given more credibility to the list

mentioned by the Anguttara Nikaya. What is significant is that the lists

emphasise that big state-like units emerged in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana,

Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bengal and Pakistan. All these Mahajanapadas were

located north of the Vindhyas.

The thing

is that Anguttara Nikaya mentions the names of Mahajanapadas that existed

before Buddha. During Buddha’s period, Kashi was annexed by Koshal and Anga by

Magadh, and thus ceased to exist. Asmaka was also probably annexed by Avanti

during this period. The listing of Vajji indicates that the statehood of Videha

had collapsed by this time.

Based on

Anguttara Nikaya, the Mahajanapadas could be grouped into two: monarchy and

republic.

1. Monarchy: Anga, Magadha, Kashi,

Koshal, Chedi, Vatsa, Kuru, Panchal, Shurasena, Asmaka, Matsya, Avanti,

Gandhara and Kamboj

2. Republic: Vajji and Malla

KASHI

Varanasi

was the capital of Kashi Mahajanapada. Varanasi was situated in the doab of the

Varuna in the north and Asi in the south. Brahmadatta was its most notable and

powerful king. He vanquished Koshal. Later, the equation changed and Kansa

annexed Kashi to Koshal.

KOSHAL

Koshal was

in the Awadh region. Shravasti was the capital of Koshal. During the Ramayana

period, Ayodhya was the capital of Koshal. During Buddha’s time, Koshal split

into two with Saket becoming the capital of the northern part and Shravasti of

the southern part. Koshal was marked by Panchal on the west, the Gandak river

in the east, Nepal in the north and River Sai in the south.

ANGA

Anga was

situated in Bihar’s Bhagalpur and Munger districts. Champa was the capital of

Anga. Champa has a unique contribution to the human history of personal

hygiene. Shampoo owes its origin to Champa. Back then it was some kind of mixed

oil that was used to clean and lubricate hair. The mixture was called Champu.

The word ‘champi’ for head massage has its origin in Champa. Champu travelled

to the west but it lost its presence and knowledge in India. Many centuries

later, champu made its way back as shampoo.

Champa’s

old name was Malini during the age of Mahabharata and Puranas. Dighanikaya

tells that Mahagovinda was the architect of Champa. Its ruler Brahmadatta

defeated Bhattiya of Magadha.

Champa has

been mentioned as one of the six metropolises of the time in

Mahaprinrvanasutra. Other metropolitan towns were Rajagriha, Shravasti, Saket,

Kaushambi and Varanasi.

MAGADHA

Magadha was

in South Bihar spread over Patna and Gaya. River Champa separated Magadha from

Anga. Rajgriha, also known as Girivraja, was the capital of Magadh. Rajgriha

was guarded by stone fortresses. It was marked by River Son in the west, Ganga

in the north, Vindhyas in the south and Champa in the east.

VAJJI

Vajji was a

federation of eight states. It has been considered as a republic by historians

– an early form of republic. Four of the eight constituents were Vajji,

Lichchhavi of Vaishali, Videha in Mithila and Jnatrika of Kundagram. The four

others were Ugra, Bhoga, Ikshvaku and Kaurava.

Vaishali

has been identified with Basadh in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur district, Videha in

Nepal’s Janakpur district and Kundagram in North Vaishali.

MALLA

Malla was

situated in Uttar Pradesh’s Deoria district. It was a federation that included

the Mallas of Pava in Padrauna district and Kushinara in Kushinagar district.

According to Kusa Jatak, Okkaka was the chief of Malla federation.

CHEDI/CHETI

Chedi was

situated in the region now known as Bundelkhand. Sotthivati was its capital. Sottivati

has been recognised as Shuktimati of Mahabharata. Shishupala was its ruler back

then. Chetiya Jataka names Upachara as one of its kings.

VATSA

Vats was

located in Uttar Pradesh’s Prayagraj (Allahabad) and Banda districts. Its

capital was Kaushambi on the bank of River Yamuna. Vishnu Purana traces the

origin of Kaushambi to Mahabharata’s Hastinapur.

Vishnu

Purana says that after Hastinapur was swept away by River Ganga, its king

Nichakshu (man without eyes) founded the city of Kaushambi. During Buddha’s

time, its ruler was Udayan of Paurava dynasty.

Puranas

identify Udayan’s father as Prantapa, who had conquered Champa. Remains of

Udayan’s royal palace and a vihara (monastery) built by Shresthi Ghoshita (also

known as Ghoshitaram) have been found at Kaushambi.

KURU

Kuru was

located in Uttar Pradesh’s Meerut, Delhi and Thanesar. Its capital was

Indraprastha. Hastinapur was within the Kuru Mahajanapada. Koravya was its

ruler during Buddha’s time. Later, a republic was established here.

PANCHAL

Panchal was

situated in Uttar Pradesh’s Bareilly, Badaun and Farrukhabad districts.

Northern Panchal had its capital in Ahichhatra in Ramnagar in Bareilly.

Southern Panchal had its capital in Kampilya in Kampil in Farrukhabad.

Famous city

of Kanyakubja was situated in Panchal. In 600 BC, Kuru and Panchal constituted

a republic.

MASTYA

Matsya

Mahajanapada was in Rajasthan’s Jaipur, Alwar and Bharatpur. Its capital was

Viratnagar, a city founded by a king named Virat.

SHURASENA

In

Brajmandal, its capital was Mathura. Ancient Greeks termed this state as

Saurasanoi and its Methora. According to Mahabharata and Purana, Shurasena was

ruled by Yadu dynasty and Krishna was its ruler.

In Buddha’s

time, Avantiputra was its ruler. He was a disciple of Buddha. His mother was an

Avanti princess, daughter of Pradyot. Avantiputra facilitated propagation of

Buddhism in Mathura.

AVANTI

Avanti was

located in western and central Malwa region. Puranas attribute the foundation

of Avanti to one of the Yadus called Haihaya. Avanti was ruled in two parts

with River Vetravati dividing the northern Avanti from southern part.

North

Avanti had its capital in Ujjayini and South Avanti in Mahishmati. North Avanti

had iron mines and Ujjayini had blacksmiths who manufactured very high quality

iron-weapons.

ASMAKA

Asmaka was

situated on the bank of River Godavari in Andhra Pradesh. Its capital was

Polti, also known by the names of Paithan, Pratishthan and Potan. Asmaka was

the only Mahajanapada of the 16 such states to have been situated in South

India. Puranas say Asmaka was founded by Ikshvaku rulers who established a

monarchy here. According to Chullakalinga Jataka, its ruler Arun had conquered

Kalinga.

GANDHARA

It is

commonly held that Afghanistan’s Kandahar has its origin in Gandhara

Mahajanapada, whose principal territories were around Peshawar and Rawalpindi

in Pakistan. Takshashila was its capital. According to Ramayana, Takshashila

was founded by Taksha, the son of Bharat.

Its second

capital was Pushkaravati. Around 600 BC, Pukkusati or Pushkarsarin was its

ruler. He established diplomatic ties with Bimbisar. He defeated Prodyot of

Avanti.

KAMBOJ

Its

principal region was South-West Kashmir including the territories of Poonch and

Kapisha that corresponds to what is known as Kafiristan extending from

Hindukush to Kabul. Its capital was Rajpur or Hataka. Later, a federal state

was established here. Kautilya has described agriculture, animal husbandry,

commerce and weapon-making as economic activities of Kambojians. Kamboj was noted

for breeding high-quality horses.

EMERGENCE OF FOUR POWERFUL MONARCHIES

The 16 Mahajanapadas in the course of time gave rise to four

powerful monarchical states. All the Mahajanapadas assimilated into one or the

other monarchies. Mutual rivalry was the force behind the annihilation of these

Mahajanapadas – a natural evolution of political power and ambition. The four

resultant monarchies were:

1.

Koshal

2.

Vatsa

3.

Avanti

4.

Magadh

KOSHAL

Koshal continued to have its capital in Shravastri,

identified with Setamohata village near Gonda in Uttar Pradesh. Before the

advent of Buddha, Kansa was the king of Koshal and had annexed Kashi to expand

his state. Mahakoshal, the son and successor of Kansa, expanded Koshal’s

territories and economic might. Gain of Kashi made Koshal a very influential

state. Kashi was an important centre of trade and hosiery. Its trade contact

with Takshashila, Sauvira and other distant places were strong. The growing

economic power of Koshal was the main reason behind its rivalry with Magadh.

During the time of Buddha, Prasenjit was the king of Koshal.

He had established friendly relationship with Magadh by marrying his sister

Mahakoshala, also known as Koshaladevi to Bimbisar. He had given Kashi or at

least a portion of it to Bimbisar in marriage as gift.

However, during the reign of Bimbisar’s son Ajatshatru,

relationship between Magadh and Koshal embittered. Samyukta Nikaya provides

details of revival of rivalry. The reason for bitterness was Kashi, which

Prasenjit had taken back after the death of Bimbisar. Prasenjit made another

move to make peace with Ajatshatru by marrying his daughter Wajira to him. He

also returned Kashi to Magadh.

During the reign of Prasenjit, Koshal was at the pinnacle of

its glory. It ruled over Shakyas of Kapilvastu, Kalam of Ksaputta, Malla of

Pava and Kushinara, Koliya of Ramagama, Moriya of Pippalivana et al. Prasenjit

was a follower of Buddha and preaching.

Prasenjit was succeeded by Vidudabh, who had usurped the

throne with the help of Dighacharan, a minister of Prasenjit. It was said that

Vidudabh was the son of a Shakya maid-servant (daasi). This became a cause of

strife between the Shakyas and Vidudabh. The maid-servant was known by the name

of Vasabhakhattiya and was married to Prasenjit.

Nothing is known about the successors of Vidudabh. Koshal

was perhaps soon annexed by Magadh.

River Rapti was an important river in Koshal. Its name back

then was Achiravati.

VATSA

Udayan was the most famous king of Vatsa. Once on hunting,

Udayan was captured by Pradyot, the king of Avanti. During his captivity,

Udayan fell in love with Pradyot’s daughter Vasavdatta and fled Avanti with

her. Later, they married and consequently, friendship between Vats and Avanti

was established.

According to Sumsumargiri (?, Bhagga republic accepted the suzerainty

of Udayan and Udayan’s son Bodhikumar resided there.

According to Bhash, Udayan had married Pdmavati, the

daughter of Darshaka, the king of Magadha – thus befriending Magadha as well.

Udayan turned to Buddhism and was initiated into it by

famous monk Pindol. This time, Kaushambi had several Buddhist mathas, the most

famous of them was Ghoshitaram’s.

AVANTI

Pradyot was its famous king. He owed his crowning to his

father Ripunjaya’s minister Pulik, who was the last Amatya or a high-ranking

minister of Magadha’s Brihadatta or Brihadrath dynasty. Pulik dethroned

Ripunjaya and installed Pradyot as the king. Buddhist text Mahavagg calls him

Chand-Pradyot signaling a strong and stubborn military policy adopted by him.

Avanti was a powerful and prosperous state due to its

richness in resources that included iron mines and blacksmith skills of its

workers. Pradyot was once treated by Magadh king Bimbisar’s physician Jeevak

for jaundice.

Pradyot was initiated into Buddhism by Mahakachchayan, a

famous monk of the time. Pradyot was succeeded by Palak, Vishakhayupa, Ajak,

Nandivardhan in sequence. They were eliminated by Shishunag of Magadh.

MAGADH

The real founder of Magadh monarchy was Bimbisar. Magadh

emerged as the most powerful empire of ancient India. Patliputra became its

imperial capital. Bimbisar’s son Ajatshatru founded Patliputra, which was built

under the supervision of his ministers Sumidha and Vassakara.

REPUBLICS IN INDIA DURING BUDDHA’S TIME

Initially, it was believed that only monarchies existed in

India. Ridge Davids was the first scholar to rediscover the existence of

republics in ancient India. Both Buddhist and Jain texts mention about the

existence of republics in various parts of india. Panini also wrote about republics.

Kautilya classifies republics into two groups:

1.

Vartashastropajivi: Those living or thriving on

agriculture, animal husbandry, commerce and weapon-making as economic

activities. Kamboja and Saurashtra were listed as examples.

2.

Rajashabdopjivi:

Those republics which used the tile of Raja for their chiefs.

Lichchhavi, Vrijji, Malla, Madra, Kukar, Panchal etc were listed as examples.

The coins of Malwa, Yaudheya and Arjunayan talk about

republics and not kings.

The

republics of the past were not the same in character that we see today. They

could be called aristocracy. The administration or statehood sought its

authority not from the masses directly but from an elite class of electors.

SHAKYAS OF KAPILVASTU

Kapilvastu

identified with Tilaurakot in Nipal was its capital. Other important towns of

the republic were Chatuma, Samagama, Khomadussa, Shilavati, Nagarak, Devadaha,

Sakkar etc.

Shakyas did

not marry outside their own blood. Buddha was from the Shakya clan. His mother

was from Devadaha. This republic was destroyed by Vidudabh, the son of Koshal

king Prasenjit by his marriage with a Shakya maid-servant.

Kapilvastu

was bordered in the north by the Himalayas, in the west and south by River

Rapti, and in the east by River Rohini.

BHAGGA OF SUMSUMAR OR

SUSHMAGIRI

Sumsumar or

Sushmagiri mountain is now identified with Chunar in Mirzapur district in Uttar

Pradesh. Bhaggas accepted the suzerainty of the Vatsas. Bodhikumar resided

here.

BULI OF ALAKAPPA

Alakappa is

identified with Shahabad-Ara-Muzaffarpur axis of Bihar. Probably, Vethadwipa

(Betia) was its capital. Bulis or Buliyas were Buddhists. Accordring to

Mahaparinirvanasutta, they acquired ashes of Buddha after his death and built a

stupa there.

KALAM OF KESAPUTTA

Kesaputta

was situated west of Koshal. Alar Kalam, one of Buddha’s early teachers who

taught him yoga and meditation, was from this state. He lived near Uruvela.

Kalama accepted suzerainty of Koshal.

KOLIYA OF RAMAGRAMA

Ramagrama

was situated east of Shakyas. In the south, it was bordered by River Sarayu.

River Rohini separated Koliyas from Shakyas. Its capital Ramagrama has been

identified with modern Ramgarh in Gorakhpur district in Uttar Pradesh. Koliyas

were famous for their police force.

MALLA OF KUSHINARA

Kushinara

is identified with present-day Kasiya. According to Balmiki Ramayana, Mallas of

Kushinara were descendents of Chandraketu, the son of Lakshamana.

MALLA OF PAVA

Pava is

identified with Padrauna in eastern Uttar Pradesh. They were militant in

nature. They fought against Ajatshatru of Patliputra by forming a federation

with Lichchhavis of Vaishali. They were defeated by Ajatshatru.

MORIYA OF PIPPALIVANA

They were a

branch of Shakyas. According to Mahavamsatika, Moriyas fled towards the

Himalayas to escape the wrath of Vidudabh, the Koshal king and the son of

Prasenjit by a Shakya maid-servant.

The fleeing

Moriyas developed Pippalivana. Here, they organised and developed peacock

rearing. Peacock, called Mayur in Sanskrit, possibly led to them being called

Moriyas, and probably developed into mighty Mauryas of Magadh empire.

Pippalivana

is identified with a village, Rajadhani near Kusumhi in Gorakhpur district of

Uttar Pradesh.

LICHCHHAVIS OF VAISHALI

Its capital

was at Basad. Lichchhavis built the famous Kuttagarshala in Mahavana, where

Buddha delivered his sermon. Lichchhavis were powerful and prosperous. In

Buddha’s time, Chetak was its ruler. His daughter Chellana was married to

Bimbisara. His sister Trishala was the mother of Mahavir Jain.

VIDEHA OF MITHILA

Videha

spread from Nepal to Bhagalpur in Bihar with Darbhanga falling in centre. Its

capital was Janakpur, in Nepal. Mithila was a famous trading centre where

traders from Shravasti would come to trade with the locals.

LAW AND ADMINISTRAION IN

REPUBLICS

Not much

information is available about enactment of law and working of administration

in these republic states.

Head or

president of the executive of the republic was an elected person or official,

called Raja. The position was held by men. His prime concern was to maintain

peace and internal coordination.

Other top officials

were Uparaja, Senapati, and Bhandagarik or treasurer. But the real power was

vested in a central committee of large membership. These members were also

sometimes called Rajas. It appears that Raja could have been the title or

address for the chief of units of administration.

According

to Ekapanna Jataka, there were 7,707 Rajas in the central committee of

Lichchhavis. In Shakyas’, the number of Rajas stood at 500.

Ekapanna

Jataka gives maximum information about Lichchhavis.

Whenever a

dispute or crisis arose, the rajas of the central committee met and decided the

course of action by voting. For example, when a dispute arose between the Shakyas

and Koshal over the Rohini river water, the Shakya’s central committee voted in

favour of war. But later when Koshal king Vidudabh laid a seize of Shakya

capital, the central committee decided to surrender to Vidudabh’s forces to end

the war accepting his lordship.

The central

committee decided the appointment of Senapati in the Lichchhavi republic. In

one instance, after the death of military commander called Khanda, the central

committee of the Lichchhavis elected Singh to be the new military commander.

Mallas of

Kushinara held a discussion in their central committee regarding Buddha’s

cremation and articles belonging to him. Buddha breathed his last in the

Kushinara.

The general

working of these republics was probably similar to modern democratic

parliaments. The working of the committee was looked after by an official

called Asannapannapaka. Literature confirms that the concept of quorum was

there. Secret ballot system for voting was prevalent. Official conducting

voting was called Shlaka-grahaka. A vote was called Chhand.

REMARKS

It is often said that the sword that Bimbisar drew from its

case was put back in the case by Ashoka in the eleventh year of his rule. By

then, the Magadh empire had reached its territorial climax.

Progression of society in history: Rig Vedic age was of the

age of tribes. There were tribal communities. Later Vedic age was of Janpadas

formed by consolidation of tribal communities. It was followed by the age of

Mahajanapadas that was characterized by bigger and massive Janapadas which were

controlled by one or more tribal communities. This was the age of the beginning

of state in India.

Mahajanapada was the highest unit of state. Information

about this age is available in literature. But literature places these

Mahajanapadas north of the Vindhyas. Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya gives the

list of 16 Mahajanapadas, all north of the Vindhyas.

Buddhist text, Diggha Nikaya’s Janavasabh Sukta gives a list

of 10 Mahajanapadas of the time. It mentions them in the pair of five. Besides

Mahajanapadas, it also talks about Janpadas, smaller units.

Other sources say that there were other Janas and

“half-civilised” tribes. Since the Mahajanapadas were in lead role, the period

is called the Age of Mahajanapadas. This was also the age of advent of Magadh

imperialism. The Mahajanapadas and Janapadas of the period did not have same

administrative system. Same administrative systems were not there even during

the Later Vedic Age. Like that, all three forms of administration continued to

be in vogue – monarchy, republican and federal. Of these, republican and

federal administrative systems were closer in nature.

These three forms of governance found practical expression

in two forms – monarchical and republican-federal mixed. Republican-federal

system were primarily found in Bihar and the terai of Nepal, and also in the

northwestern region of India.

Government in Surasena and Chedi were essentially federal in

nature. Vajji and Mala had republican form of government. Bihar and Nepal’s

terai were important regions for republican governments. Such states were:

- Shakya of Kapilvastu

- Buliya of Alakappa

- Koliya of Ramagrama

- Malla of Pava

- Malla of Kushinara

- Moriya of Pippalivana

- Lichchhavi of Vaishali

- Nay/Nath of Vaishali

- Kalam of Kelaputra (New Vaishali)

- Magga of Sushmagiri

Videh of Mithila is also spoken in the same vein of

republican government. All these republics were in North Bihar and the terai of

Nepal. They were numerous and some of them had formed a federation. One such

federation was Vajji Federation, which comprised of most republics of the

region. The federation was formed for security or protection and facilitation

of civic works.

They felt threatened from monarchical governments or states.

There were several Janapadas that followed monarchical form of government but

four were more influential. They were:

-

Magadh Mahajanapada of Girivraj or Rajgriha

-

Vatsa Mahajanapada of Kaushambi

-

Koshal Mahajanapada of Ayodhya-Shravasti

-

Avanti Mahajanapada of Ujjaini or Mahishmati

These four Mahajanapadas were special in military power.

They were efficient in the use of iron. They believed in the principle of

centralization of power. They followed the principle of expansion in foreign

policy.

During this period, these four Mahajanapadas expanded their

territories at the cost of the Janapadas, Mahajanapadas and Janas irrespective

of their form of government, monarchical or republican.

Of these, the position of Magadh Mahajanapada was different

from other three due to specific reasons:

- Geographic

- Economic

- Military

- Technological

- Degree of propensity of centralization of power

Magadha Mahajanapada saw continued expansion of its

territories due to these factors. Its size continued to increase. The expansion

process that began in sixth century BC continued till fourth century BC almost

without a break. The expansion happened at the cost of others.

Propensity of expansion remained a constant with the Magadh

Mahajanapada even though the ruling dynasty kept changing. Magadh was ruled by

Haryanka dynasty, followed by Shishunag and Nanda ruling families. But change

of dynasties did not bring a change in expansion policy.

The Maurya dynasty took the Magadh dynasty’s expansion to

its climax. Due to the dominance of Magadh Mahajanapada during this period, it

is also known as the age of the rise and growth of Magadh imperialism.