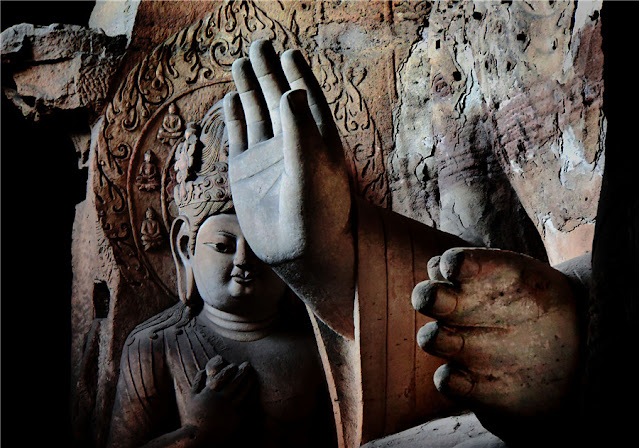

| Kailash Temple, Aurangabad, Maharashtra: Carved from one piece of rock, estimated to have weighed over 4 lakh tonnes, during the reign of Rashtrakuta king Krishna I (Photo: Twitter/@ancient_bharat) |

Kailash

Temple, Aurangabad, Maharashtra: Carved from one piece of rock, estimated to

have weighed over 4,00,000 tonnes during the reign of Rashtrakuta king Krishna

I. (Photo: Twitter/@ancient_bharat)

Three

powerful kingdoms arose in India between 750 and 1000. These were the Pala

kingdom, the Pratihara kingdom and the Rashtrakuta kingdom. Each of these

kingdoms, although they fought among themselves, provided stable conditions of

life over large areas and gave patronage to arts and letters. Of the three, the

Rashtrakuta empire/kingdom lasted the longest. It was not only the most

powerful empire of the time but also acted as a bridge between the North and

the South India in economic as well as cultural matters.

STRUGGLE FOR DOMINATION

Since the

days of Harsha, Kannauj was considered the symbol of sovereignty of North

India. Control over Kannauj also implied control of the upper Gangetic valley

and its rich resources in trade and agriculture. The Palas and the Pratiharas

clashed with each other for the control of area extending from Benaras to

Jharkhand which again had rich natural resources, and well-developed

traditions. The Pratiharas clashed with the Rashtrakutas too.

THE PALAS

The Pala

empire/kingdom was founded by Gopala, in or around 750, when he was elected by

the notable men of the area to end anarchy prevailing there. He was succeeded

by Dharmapala. In spite of having been defeated by Dhruva Rashtrakuta,

Dharmapala occupied Kannauj and held a grand durbar there. It was attended by

vassal rulers from Punjab, eastern Rajasthan etc. However, Dharmapala could not

consolidate his control over Kannauj. Nagabhatta II Pratihara defeated him near

Mongyr (now, Munger).

Bihar and

eastern Uttar Pradesh remained a bone of contention between the Palas and the

Pratiharas. Bihar and Bengal remained, however, under the control of the Palas

for most of the period of their rule.

Failure in

the north compelled the Pala rulers to turn their energies in other directions.

Devapala (810-850), the successor of Dharmapla, extended his control over

Pragjyotishpur (Assam) and parts of Odisha. A part of Nepal probably also came

under the Pala suzerainty.

Thus, for

about a hundred years, the Palas dominated eastern India. Their power is

attested by Arab merchant Sulaiman. He calls the Pala kingdom Ruhma and

testifies that the ruler maintained a large army.

The Tibetan

chronicles also provide some information about the Palas. The Pala rulers were

great patrons of Buddhist learnings and religion. Dharmapala revived the famous

university of Nalanda. He set apart 200 revenue villages for meeting the

expenses of the university. Dharmapala also founded the Vikramshila university,

which stood second only to the Nalanda university in fame.

The Palas

built many viharas in which a large number of Buddhist monks lived. The Pala

rulers had a very close cultural relation with Tibet. The noted Buddhist

scholars, Shantarakshita and Dipankara (also called Atisa) were invited to

Tibet. They introduced a new form of Buddhism there. As a result, many Tibetan

Buddhists flocked to the universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila for education.

The Palas

had close trade contacts with South East Asia. Trade with South East Asia was very

profitable adding immensely to prosperity of the Pala rulers and empire. The

powerful Shailendra dynasty of South East Asia sent an embassy to the Pala

court and sought permission to build a monastery at Nalanda and also requested

the Pala ruler Devapala to endow five villages for its upkeep. The request was

granted. It bears the testimony to a close relationship between the two

empires/countries in the early medieval times.

THE PRATIHARAS

The

Pratiharas are also called the Gurjar-Pratiharas. They are said to have

originated from Gujarat or South West Rajasthan. They were at first possibly

local officials but later able to carve out a series of principalities in

central and eastern Rajasthan. They gained prominence on account of their

resistance to Arab incursions from Sindh into Rajasthan. The efforts of the

early Pratiharas to extend their control over the upper Gangetic valley and

Malwa region were foiled by the Rashtrakuta rulers Dhruva and Gopal III.

The real

founder of the Pratihara empire was Bhoja, who was also the greatest ruler from

the dynasty. Re rebuilt the empire and recovered Kannauj around 836. Kannauj

remained the capital of the empire for almost a century. The name of Bhoja is

famous in many legends. Bhoja was a devotee of Vishnu and adopted the title of

Adivaraha, which has been found inscribed in some of his coins.

Mihir Bhoja

was succeeded by Mahendrapala I, probably in 885. Mahendrapala I maintained the

empire of Bhoja till 908-09 and extended it over Magadha and North Bengal.

Mahendrapala I fought a battle with the king of Kashmir but had to yield to him

some of his territories in Punjab won by Bhoja.

The

Pratiharas, thus, dominated North India for over a hundred years — middle of

the 9th century to the middle of the 10th century. The Arab travellers tell us

that the Pratiharas had the best cavalry in India, having horses imported from

Central Asia. Al Masudi, who visited Gujarat in 915-16, testifies about the

great power and prestige, and vastness of the Pratihara emepire. He calls the

Gurjara-Pratihara kingdom Al Juzr, and identifies Baura (possibly out of

confusion for Bhoja, who had died by that time) as its king.

The

Pratiharas were patrons of learning and literature. The great Sanskrit poet and

dramatist Rajashekhar lived at the court of Mahipala, a grandson of Bhoja. The

Pratiharas also embellished Kannauj with many fine buildings and temples.

Between 915

and 918, Indra III Rashtrakuta attacked Kannauj and devastated the city. This

weakened the Pratihara empire, and possibly also resulted in Gujarat being

passed to the hands of the Rashtrakutas. Al Masudi tells us that the Pratihara

empire had no access to the sea. The loss of Gujarat was a major blow to the

Pratiharas.

Again in

963, Krishna II Rashtrakuta invaded North India and defeated the Pratihara

army. This was followed by rapid dissolution of the Pratihara empire.

THE RASHTRAKUTAS

The dynasty

of the Rashtrakutas produced a long line of warriors and able administration.

The kingdom was founded by Dantidurg, who set up his capital at Manyakhet. The

Rashtrakutas kept fighting with the Pratiharas, the Palas, the Chalukyas of

Vengi, the Pallavas of Kanchi and the Pandyas of Madurai.

Probably,

the greatest rulers of the Rashtrakutas were Govind-III and Amoghvarsha. Govind-III

defeated the Kerala, the Pandyas, the Chola, the Pallava and the western Ganga

kings.

The king of

Lanka and his minister were brought to Halapur. Two statues of the lord of Sri

Lana were carried to Manyakhet and installed like pillars of victory in front

of a Shiva temple.

Amoghvarsha

preferred the pursuit of religion and literature to war. He was himself an

author and credited with writing the first Kannada book on poetics. He was a

great builder. He is said to have built the capital city of Manyakhet to

surpass the glory of the city of Lord Indra. However, there were many

rebellions in the far flung parts of the kingdom during Amoghvarsha’s reign.

These could barely be contained, and began afresh after his death.

Indira-III

re-established the empire. Indra-III was the most powerful king of his times.

Al-Masudi has mentioned about a Rashtrakuta king with name, Balhara or

Vallabharaja as the greatest king of India.

Krishna-III

was the last in the line of brilliant rulers from Rashtrakuta lineage. He pressed

down to Rameshwaram where he set up a pillar of victory. But after his death,

al his opponents united against his successor. In 972, the Rashtrakuta capital

Malkhed was sacked and burnt. This marked the end of the Rashtrakuta rule.

The

Rashtrakuta rulers were tolerant in their religious views and patronised not

only Shaivism and Vaishnavism but also Jainism. The famous rock-cut temple of

Shiva at Ellora was built by Krishna-I in the ninth century.

The

Rashtrakutas allowed Muslim traders to settle, and permitted Islam to be

preached in their dominions. Muslims had their own headmen and held their daily

prayers in large mosques in many of the coastal towns in the Rashtrakuta

empire. This tolerant policy helped to promote foreign trade which enriched the

Rashtrakutas.

The

Rashtrakuta kings were great patrons of art and letter. Their court poets wrote

in Sanskrit, Prakrit and Apabhramsa. The great Apabhramsa poet, Swayambhu

probably lived in the Rashtrakuta court.

POLITICAL IDEAS AND

ORGANISATION

The system

of administration in the three empires was based on the idea and practices of

the Gupta empire, Harsha’s kingdom and the Chalukyan kingdom.

Monarch was

the head of all affairs. He was the head of the administration and the

commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The infantry

and cavalry stationed in his courtyard. Captured war-elephants were

paraded in front of him. He was attended by royal chamberlains, who regulated

the visits of the vassal chiefs, feudatories, ambassadors and other high

officials. The king also dispensed justice. Dancing girls and skilled musicians

also attended the court. Ladies of the king’s household also attended the court

on festive occasions.

The king’s

position was hereditary. Thinkers of the time emphasised absolute loyalty and obedience

to the kings because of the insecurities of the time. However, a contemporary

writer, Medhatithi thought that it was the right of an individual to bear arms

in order to defend oneself against thieves and assassins. He also said that it

was right to oppose an unjust king.

The rules

of succession were not rigidly fixed. Thus, Dhruva and Govinda-IV deposed their

elder brothers. Sometimes, rulers designated the eldest son or another

favourite son as Yuvraj. In that case, Yuvraj stayed at the capital and helped the

king in the task of administration. Younger sons were sometimes appointed as

the provincial governors. Princesses were rarely appointed to government posts

but there is an instance where a Rashtrakuta princess named Chandrobalabbe, a

daughter of Amoghvarsha, administered the Raichur doab region for some time.

Kings were

generally advised by a number of ministers, who were chosen by the king usually

from leading families. Their position was often hereditary. During the Pala

dynasty’s reign, a Brahmana family supplied four successive chief ministers to

Dharamapala and successors.

From

epigraphic and literary records, it appears that in almost every kingdom, there

was a minister, treasurer, chief (senapati) of the armed forces, chief justice

and purohita.

More than

one post was combined in one person. All ministers except Purohita were

expected to lead military campaigns where called upon to do so. There were also

officials of the royal household, Antahpur.

Arab

travellers tell us that the three kingdoms maintained highly efficient military

wings. Elephants were supposed to be the elements of strength and were greatly

prized. The largest number of elephants was maintained by the Pala kings.

A large

number of horses were imported by Rashtrakuta and Pratihara kings by sea from

Arabia and West Asia, and by land from Central Asia. The Pratihara kings are

believed to have had the finest cavalry in the country. There are no references

to war chariots which had fallen out of use.

Some of the

kings, especially the Rashtrakutas had a large number of forts. The infantry

consisted of regular and irregular troops and units provided by vassal chiefs

as levies.

The regular

troops were often hereditary and sometimes drawn from all over India. Thus, the

Pala infantry consisted of soldiers from Malwa, Khasa (Assam), Lata (South

Gujarat) and Karnataka. The Pala kings and perhaps the Rashtrakutas had their

own navies.

The empires

consisted of areas administered directly and regions ruled by vassal chiefs.

The latter were autonomous as far as their internal affairs were concerned and

had a general obligation of loyalty, paying a fixed tribute and supplying a

quota of troops to the overlord. The vassal chiefs were required to attend the

court of the overlord on special occasions and sometimes, they were required to

marry one of their daughters to the overlord to one of his sons.

But the

vassal chiefs always aspired to become independent, and wars were frequently

fought between them and the overlord. Thus, the Rashtrakuta had to fight

constantly against the vassal chiefs of Vengi (Andhra) and Karnataka. The

Pratihars had to fight against the Paramaras of Malwa and the Chandellas of

Bundelkhand.

The

directly administered areas in the Pala and the Pratihara empires were divided

into Bhuktis, and Mandalas or Vishayas. The governor of a province was called

Uparika, and the head of a district Vishayapati.

The Uparika

was expected to collect land revenue and maintain law-and-order with the help

of the army. The Vishayapati was also expected to do the same within his

jurisdiction.

During this

period, there was an increase of smaller chieftains called Samantas or

Bhogapatis who dominated over a number of villages. The Vishyapatis and these

smaller chiefs tended to merge with each other and later on, the word Samanta

began to be used indiscriminately for both of them.

In the

Rashtrakuta kingdom, the directly administered areas were divided into Rashtra

(provinces), Vishayas and Bhuktis. The head of a Rashtra was called the rashtrapati,

and he performed the same functions as the Uparika. The head of a Vishaya here

was called Pattala.

Below these

territorial units was a village, which was the basic unit of administration.

The village administration was carried on by the village headman and the

village accountant whose posts were generally hereditary. They were paid by

grants of rent-free lands.

The headman

was often helped in his duties by the village elder called Grama-Mahajana or

Grama-Mahamattara. In the Rashtrakuta kingdom particularly in Karnataka, there

were village committees to manage local schools, tanks/ponds, temples and

roads. They could also receive money or property in trust and manage them.

These

committees worked in close cooperation with the village headmen and received a

percentage of the revenue collection. Simple disputes were also decided by

these committees.

Towns also

had similar committees to which the heads of the guilds wee also associated.

Law-and-order in the towns and in their immediate locality was the

responsibility f the Koshta-pala in the towns.

(Source: History books and notes from CSE preparation days)