Saturday, August 20, 2022

If nuke does not kill you, famine will... a total of 5 bn

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Saturday, July 30, 2022

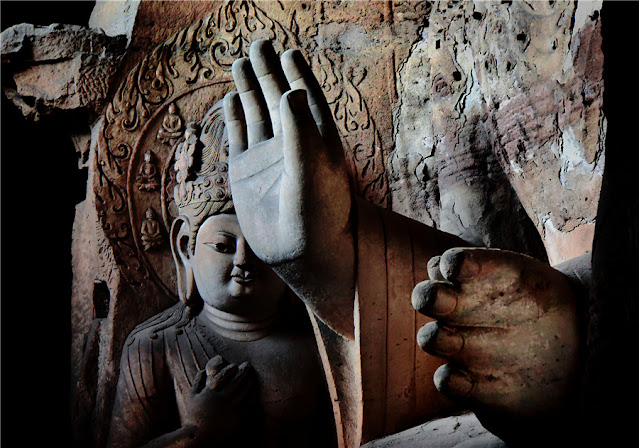

Ashoka's Dhamma and his rock edicts: A recap

Maurya emperor Ashoka riding a chariot in a Sanchi Stupa relief (Photo: Twitter)

Ashokan

policy of Dhamma has been a topic of lively discussion and the best source to

know about his Dhamma is his edicts. The edicts were primarily written to

explain to the people the principles of Dhamma. What comes out from his edicts

is that the Dhamma was not any particular religious faith or practice. It was

also not an arbitrarily formulated royal policy. Dhamma related to the norms of

social behaviour and activities in a very general sense and in his Dhamma,

Ashoka attempted a very careful synthesis of various norms which were current

in his times.

The Dhamma

had a historical background that served as a set of causes effecting in an

official policy of one of the most powerful kings the world has seen.

SOCIOECONOMIC BACKGROUND

The Mauryan

period witnessed a change in the economic structure of society largely due to

the increasing use of iron. It has generally been argued that the use of the

Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) pottery is an indicator of material

prosperity of the period.

The use of

punch-marked coins of silver and some other varieties of coins, the conscious

intervention of the state to safeguard trade routes and the rise of urban

centres point to a structured change in the economy. It required necessary

adjustments in society.

The

commercial classes had also come to the forefront. The emergence of urban

culture by its very logic demanded a more flexible social organisation.

The

incorporation of tribes and peoples from the outlying areas into the social

fabric also presented a problem. The rigidity of the Brahmanical class

sharpened the division within society. The lower orders turned to various

heterodox sects and this created social tensions.

It was this

socioeconomic situation which emperor Ashoka inherited when he ascended the

Mauryan throne.

RELIGIOUS BACKGROUND

The

Brahmanical hold over society was increasingly coming under severe attack. The

privileges of the priests, the rigidity of the caste system and elaborate

rituals were being questioned. The lower orders among the four caste-classes

began to favour new sects. The opposition to the Brahmanism by the commercial

class was to give a fillip to the other sects of society.

On the

other hand, Buddhism opposed the dominance of the Brahmanas and the concept of

sacrifice and rituals. Buddhism had begun as a schismatic movement from the

more orthodox Brahmanism. Its fundamentals were based on an emphasis on misery

and advocacy of the middle path. It appealed to the lower orders and to the

emerging social classes. The humane approach to relations in society preached

by Buddhism further attracted different sections to Buddhism. Ashoka’s Dhamma

bore deep influence of Buddhism.

POLITICAL BACKGROUND

By the time

Ashoka ascended the throne, the state system of Mahajanapadas had grown very

elaborate and complex from where it had started during the Mahajanapada era.

Now, there

was political supremacy of one region (Magadha) over a vast territory which

comprised many previous kingdoms, gana-sanghas and areas where no organised

states had existed before.

Within this

vast territory, there was existence of various geographical regions, cultural

areas and different beliefs, faiths and practices.

There was

monopoly of fore by a ruling class of which the emperor was the supreme head.

The state

appropriated a very substantial quantity of surplus from agriculture, commerce

and other sources.

A large

administrative apparatus was developed for governing the people and

territories.

The

complexity of the state system demanded an imaginative policy from the emperor

based on minimal use of force in such a large empire having diverse forms of

economy and religions. It could not have been controlled by an army alone. A

more feasible alternative was the propagation of a policy that would work at an

ideological level and reach out to all sections of society.

The policy

of Dhamma was such an endeavour. Obviously, the policy of Dhamma was an earnest

attempt at solving some of the problems a complex society faced. However, it is

also true that Ashoka’s personal beliefs and his own perception of how he

should respond to the problems of his empire were responsible for the

formulation of the policy of Dhamma.

CONTENTS OF DHAMMA

The

principles of Dhamma were so formulated as to be acceptable to people belonging

to different communities and following any religious sect. Dhamma was not given

any formal definition or structure. It emphasised on toleration and general

behaviour of people. Its emphasis in particular was on dual toleration – of

people themselves and also their various beliefs and ideas.

There is

stress on showing consideration towards slaves and servants, obedience to

elders, and generosity towards the needy, Brahmanas and Shramanas. Ashoka prescribed

tolerance of different religious sects in an attempt to create a sense of

harmony.

The policy

of Dhamma also laid emphasis on non-violence, which was to be pracised by

giving up war and conquests, and also as a restraint on killing of animals.

However, Ashoka was conscious that display of his political and military might

up to a certain degree could be necessary to keep his empire intact and certain

sections of people, especially some primitive forest tribes in check.

The policy

of Dhamma included certain welfare measures such as planting of trees, digging

up of wells etc. Ashoka denounced certain ceremonies and sacrifices practised

regularly on various occasions as meaningless.

A group of

officers known as the Dhamma Mahamattas were instituted to implement and

publicise various aspects of Dhamma. Ashoka thrust a very special

responsibility on them to carry his messages to various sections of society.

However, they seem to have developed into a type of priesthood of Dhamma with

great powers and soon began to interfere in politics as well.

DHAMMA AS PER MAJOR ROCK EDICTS

Major Rock Edict-I

It declared prohibition of animal

sacrifice and holiday festive gatherings.

Major Rock Edict-II

It related to certain measures of social

welfare which were included in the working of Dhamma. It mentioned medical

treatment for men and animals, construction of roads, wells and planting of

fruit-bearing trees and medicinal herbs.

Also talked about states outside the

boundaries of Magadh empire: Pandyas, Satyapuras and Keralaputras of South

India.

Major Rock Edict-III

It declared that liberality towards

Brahmanans and Shramanas is a virtue. Respect to mother and father is a good

quality to have. Empire officials Yuktas, Pradeshikas and Rajukas would go

every five years to different parts of his empire to spread Dhamma.

Major Rock Edict-IV

Dhammaghosha (bugle of righteousness or

Dhamma) over Bherighosha (bugle of war). It said that due to the policy of

Dghamma, the lack of morality and disrespect towards Brahmanas and Shramanas,

violence, unseemly behavior towards friends, relatives and others, and evils of

this kind have been checked. The killing of animals to a large extent was also

stopped.

Major Rock Edict-V

It referred to the appointment of Dhamma

Mahamattas for the first time in the twelfth year of his reign. These special

officers were by the emperor to look after the interests of all sects and

religions and spread the message of Dhamma in each nook and cranny of the

state. The implementation of the plicy of Dhamma was entrusted in their hands.

It talked about treating slaves right

and humane.

Major Rock Edict-VI

It was an instruction to Dhamma

Mahamattas. They were told that they could bring their reports to the emperor

at any time, irrespective of whatever activity he may be engaged in. the second

part of the edict dealt with speedy administration and smooth transaction of

business.

Major Rock Edict-VII

It talked the necessity of tolerance

towards different religions among all sects, and welfare measures being

undertaken by the emperor/empire for the public not only within the Magadhan

territories but in his neighbouring kingdoms as well.

Major Rock Edict-VIII

It talked about Dhammayatras saying that

the emperor would undertake these tours instead of traditional hunting

expedition to improve and deepen his contact with various sections of people of

the empire.

It mentioned about Ashoka’s first visit

to Bodh Gaya and Bodhi Tree, giving importance to Dhamma Yatra.

Major Rock Edict-IX

It attacked ceremonies performed at

birth, illness, marriage and before setting out for a journey. A censure was

passed against ceremonies observed by wives and mothers. Ashoka instead laid

stress on the practice of Dhamma and usefulness of ceremonies.

Major Rock Edict-X

It denounced fame and glory, and

reasserted the merit of following the policy of Dhamma.

Major Rock Edict-XI

It is a further explanation of Dhamma

with emphasis on showing respect to elders, abstaining from killing animals,

liberality towards friends and being humane towards slaves and servants.

Major Rock Edict-XII

Similar to MRE-VIII, it reflected the

anxiety of Emperor Ashoka that he fled owing to conflict between competing sects

and carried instructions for maintaining harmony.

It mentioned about Ithijika Mahamatta,

the high-ranking official in charge of women’s welfare.

Major Rock Edict-XIII

It is of paramount importance in

understanding the Ashokan policy of Dhamma. It prescribed conquests by Dhamma

instead of war. This was a logical culmination of the thought process which

began with the first MRE. This is Ashoka’s testament against war. It

graphically depicted the tragedy of war.

This MRE was issued at the end of the Kalinga

War bearing testimony to how Ashoka underwent a change in heart from an being aggressive

and violent warrior to a preacher of peace and Dhamma.

It gave details of Magadha’s victory

over Kalinga and mentioned Ashoka’s Dhamma Vijay over Greek kings Antiochus of

Syria (Amtiyoko), Ptolemy of Egypt (Turamaye), Magas of Cyrene (Maka),

Antigonus of Macedon (Amtikini), Alexander of Epirus (Alikasudaro). It also

mentioned about Pandyas and Cholas in South India.

There is another MRE, the fourteenth. It

entailed the purpose of rock edicts – to spread Dhamma and policies of the

emperor.

PS: Ashoka put out his instructions

through a series of edicts inscribed on rocks installed across his empire.

These edicts are categorized by historians into five simpler groups:

-

Major Rock Edicts

-

Minor Rock Edicts

-

Separate Rock Edicts

-

Major Pillar Edicts

-

Minor Pillar Edicts

There are altogether 33 inscriptions

that have been found in the edicts recovered/survived so far.

ASHOKA’S DHAMMA AND HIS STATE

Ashoka’s

Dhamma was not simply a collection of lofty and feel-good phrases. He

consciously adopted Dhamma as a matter of state policy.

It was a

major departure from Arthashastra, the political treatise that formed the basis

of kingship during Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the dynasty. In the

Arthashastra, the king owed nothing to anyone. His only job was to rule the

state efficiently.

But

Ashoka’s Dhamma was a state policy. He declared that “all men are my children”

and “whatever exertion I make, I strive only to discharge the debt that I owe

to all living creatures”. It was totally a new and inspiring ideal of kingship.

Ashoka

wanted to conquer the world through love and faith and hence he sent many

missions to propagate Dhamma to even far flung places such as Egypt and Greece

besides relatively nearby Sri Lanka.

The

preparation of Dhamma included several measures for people’s welfare. Centres for

medical treatment of men and animals/beasts were founded inside and outside the

empire. Shady groves, wells fruit orchards and rest houses were laid out. This

kind of charity work was a radically different attitude from the king of

Arthashastra, who would not incur any expenses unless they brought more

revenues in return.

Ashoka

prohibited useless sacrifices and certain forms of gatherings which led to

waste, and indiscipline and superstition. He recruited Dhamma Mahamattas for

that purpose. They were to see to it that people of different sects were

treated equally and fairly. Moreover, they were also asked to look after the

welfare of prisoners. Many of the convicts who were kept in fetters after their

sentence had expired were to be released. Those sentenced to death were to be

given a grace for three days.

Ashoka

launched Dhamma Yatra, righteous tours. He and his high-ranking officials were

to tour the country in order to propagate Dhamma and establish direct contact

with his subjects.

Ashoka

renounced war and conquest by violence, and forbade killing of many animals.

Ashoka himself set an example of vegetarianism by almost stopping consumption

of meat in his royal household.

It was

because of such attitudes and policies that modern writers like Kem called him

“monk in a king’s garb”.

DHAMMA: INTERPRETATION

It has been

suggested that it was the original Buddhist thought that was being preached by

Ashoka as Dhamma, and later on, certain theological additions were made to

Buddhism. This kind of thinking is based on Buddhist chronicles. But

definitely, Ashoka did not favour Buddhism at the expense of other religious

beliefs.

Ashoka’s

creation of the institution of Dhamma Mahamatta indicates that Ashoka’s Dhamma

was not to favour any particular religious doctrine. Had that been the case,

there would not have been any need for such an official as Ashoka could have

utilised the organisation of Sangha to propagate Dhamma.

Further,

Ashoka wanted to promote tolerance and respect for all religious sects, and

duty of the Dhamma Mahamattas included working for Brahmanas and Shramanas.

Some

historians have suggested that Ashoka’s banning of sacrifices and the favour

that he showed to Buddhists led to Brahmanical reaction, which, in turn, led to

the decline of the Mauryan empire. Others believe that the stopping of wars and

emphasis on non-violence crippled the military might of the empire. This led to

the collapse of the empire, after the death of Ashoka.

However,

Romila Thapar has shown that Ashoka’s Dhamma, apart from being a document of

his humanness, was also an answer to the socio-political needs of the

contemporary situation.

That it was

not anti-Brahmanical is proven by the fact that respect for Brahmanas and

Shramanas was an integral part of Ashoka’s Dhamma. His emphasis on non-violence

did not blind him to the needs of the state. He warned the Atavikas (forest

tribes) of using the military force of the empire if they did not mend their

ways.

Ashoka’s

‘no to war’ policy came at a time when his empire had almost reached its

natural boundaries. In the deep south, he had friendly ties with the Cholas and

the Pandyas. Sri Lanka was an admiring ally. The policy of tolerance was a wise

course of action in an ethnically diverse, religiously varied and class-divided

society.

Ashoka’s

empire was a conglomerate of diverse groups. There were farmers, pastoral

nomads and hunter gatherers besides a burgeoning urban population. There were

Greeks, Kamobjas and Bhojas, and hundreds of groups following divergent

traditions.

In such a

society and political composition, the policy of tolerance was the need of the

hour. Ashoka tried to transcend the parochial cultural traditions by a broad

set of ethical principles. It is, therefore, obvious that he was not

establishing a new religion. He was simply trying to impress upon his society

to guide along ethical and moral principles that suited his politics quite

well.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Factors Affecting Ocean Currents

|

| Ocean currents across seas (Photo: Windows to the Universe) |

Ocean currents follow a fixed pattern of movement, which is controlled or influenced by the following set of factors.

I. Factors in relation to the earth’s nature

a. Gravitational force

b. Deflective force by the earth’s rotation

II. Ex-oceanic factors

a. Atmospheric pressure and its variation

b. Wind and frictional force or planetary winds

c. Precipitation

d. Nature of evaporation and insolation [amount of solar radiation falling onto a particular area of the earth]

III. Sub-oceanic factors

a. Pressure gradient

b. Temperature differences

c. Salinity

d. Density

e. Melting of ice

IV. Other factors modifying the ocean currents

a. Direction and shape of the coastlines

b. Seasonal variation

c. Bottom topography or configuration

The gravitational pull increases towards the poles. This pull has two effects on the flow of ocean water. First, it compresses water body a bit more towards the poles making a level-gradient fro ocean water and as a result water moves towards the poles.

Secondly, the pull creates a centripetal force towards the earth’s centre but as the ocean floor obstructs water to reach destination, the ocean water starts moving horizontally in its attempt to reach the destination [the vector resolution rule].

The earth’s rotation deflects freely moving objects including ocean currents to the right. In the northern hemisphere, this is a clockwise direction, e.g. the circulation of the Gulf Steam and Canary current. In the southern hemisphere, this is anti-clockwise direction, e.g. Brazilian current, and the West Wind Drift.

Over the regions of greater atmospheric pressure, the level of the sea is found to be lowered and vice versa due to compressional phenomenon. Therefore, ocean water flows from higher level to lower level, that is, from low air pressure region to high air pressure zone. For example, Canary current flows from sub-polar low air pressure zone to sub-tropical high air pressure region.

Prevailing winds are perhaps the most influential factors of the flow of the ocean water. Trade Winds move equatorial waters westward and warm the eastern coasts of the continents and resultantly force equatorial waters to move towards the poles when obstructed by continental masses. For example, the NE Trade Winds move the North Equatorial Current and its derivatives, the Florida Current and the Gulf Stream Drift to warm the southern and eastern coasts of the US.

Similarly, the SE Trade Winds drive the South Equatorial Current which warms the eastern coast of Brazil as the warm Brazilian Current. The westerlies of of the temperate latitude result in a north-easterly flow of water in the northern hemisphere, e.g. the movement of North Atlantic Drift.

In the southern hemisphere, westerlies drive the West Wind Drift all around the globe and where obstructed by continental mass give rise to distinct ocean currents — the Peruvian Current towards equator off South America, Benguela Current off South Africa and West Australian Cold Current off Australia.

The strongest evidence of prevailing winds impacting the ocean current flow is seen in the North Indian Ocean. Here, the direction of currents changes completely with the direction of the monsoon winds.

Main ocean currents and the relevant prevailing are as follows:

|

Ocean Currents |

Prevailing Winds |

|

North Equatorial Warm Current |

NE Trade Winds |

|

South Equatorial Warm Current |

SE Trade Winds |

|

Counter-equatorial Warm Current |

Counter-equatorial Westerlies |

|

North Atlantic Drift |

Westerlies |

|

North Pacific Current |

Westerlies |

|

West Wind Drift |

Westerlies |

Ocean regions receiving excessive additional water on account of greater amount of precipitation serve as the source regions of ocean currents, for example, the movement of equatorial warm currents to higher latitudes. The Gulf Stream, the Brazilian Current, East Australian Current, Kuro Siwo Current have their source in the equatorial ocean water due to excessive rains.

Differences in the distribution patterns of insolation and amount of evaporation over oceans lead to formation of a current. Insolation and evaporation at an oceanic place work in tandem and where its combined effect is less than the supply of water/precipitation, the current flow starts from there. Thus, current flows from equatorial zone to the temperate zone which also receives current from the polar zone due to the same reason.

Sub-oceanic pressure gradient also causes the flow of ocean water. But it is more important for vertical movement than the horizontal movement. However, temperature difference does play a major role. As warm air is lighter and rises higher than cooler air, ocean water gathers more along equatorial zone and as a consequence, the warm equatorial current/water moves along the surface slowly towards the poles. The heavier cold water of the polar region creeps slowly along the bottom of the sea towards the equator.

Salinity of ocean water varies from place to place. Waters of high salinity are denser than waters of low salinity. Hence, waters of low salinity flow on the surface of waters of high salinity or towards the regions of high salinity. At the bottom of the ocean, the flow is reversed. Hence, the Atlantic waters enter the Mediterranean Sea at surface and return at the bottom.

Density being the sum total of temperature, pressure and salinity directly controls an ocean current. Low density waters flow towards high density waters’ zone. Hence, waters from mid and low latitudes flow towards high latitudes. Similarly, warm waters flow towards cold waters.

Melting of ice adds fresh volume of water to the ocean in higher latitudes and as a result, it flows towards low latitudes, e.g. cold currents emerging from the Artic region — Labrador and Oya Siwo are cold currents.

Costal form modifies the direction of a current to some extent. The westward movement of the South Equatorial Current is obstructed by the Cape San Roque of South America bifurcating it into the Caribbean Stream and the Brazilian Current.

Changing seasons also bring some impact of current flow worldwide in terms of latitudinal shift of ocean currents. But the most remarkable impact is seen in the Indian Ocean where there is complete reversal of ocean current under the impact of the monsoonal winds of different seasons.

Bottom topography of ocean also determines the direction of ocean currents, especially the impact of mid-oceanic ridge is more pronounced. It is very apparent in the Atlantic Ocean where North Equatorial Current, whose normal range of flow is 0-12-degree latitude, is deflected northward even up to 25-degree latitude due to the presence of the mid-oceanic ridge.

It is therefore obvious that the origin and maintenance of ocean currents are influenced by a large number of factors but the most interesting part of this phenomenon is that none of the factors can be studied or taken alone as far as ocean currents’ flow is concerned.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Sunday, June 26, 2022

Why India got socio-religious reformers 600 years before Christ

|

| Vardhman Mahavira |

Jesus Christ was born in 6 BCE (before common era). His religious teachings heralded a socio-religious revolution in the West. He preached peace to an extremely quarrelsome population from the deserts of Arab to the greeneries of Greece and Italy. But historians tell us that the real impact of the Christ revolution happened after Jesus Christ's teachings hit the head of Constantine One or Constantine, the Great.

Though some historians doubt his absolute belief in Christianity but they agree that he identified himself as a Christian. One particular incident is often cited. That when he was leading his army to fight off an invader, a pagan, just outside Rome in the early fourth century (311-12), he saw an image in the sky. As the narrative goes, his enemy believed in a prophesy that the enemies of Rome would prevail in the war. Constantine, on the other hand, saw an image in the sky -- Chi-Ro (kee-ro), represented by two Greek letters -- x and p -- combined together with words inscribed on air: by this sign, conquer.

He led his army to victory. The next year, he declared persecution of Christians illegal in Rome. He made Chi-Ro the official insignia of his army, which won many a battle, vastly expanding the Roman empire, and made Byzantine his capital christened as Constantinople, now Istanbul. This Chi-Ro later became the Christian Cross for the Christian armies. The impact of his deeds was such that Christianity was declared the official religion of Rome seventy years later.

This story is originally very long. I have tried to tell it in short. Even this abridged version is lengthy for a write-up on how socio-religious movements happened in India many a centuries before Christianity made a true impact in the West. But I told this story on purpose. Most people need a reference point or a familiar background against which they appreciate some intrinsically known facts. We tend to get used to the worst and the best almost in the same mental-psychological manner. We just get used to it.

I had read somewhere that when Mahavira and Buddha happened to the Indian subcontinent, there were more than 560 (562, if I remember correctly) socio-religious reformers of repute. This was happening more than 500 years before Christ was born, and more than 800 years before Christianity began taking its real shape. And unlike Christianity, the most popular religion on the planet, none of these socio-religious philosophies needed an army to stamp their authority on the minds of the then-Indian population. All of them received respect from people even though many of them fought among themselves in their bid to establish superiority of their own philosophy.

So, the natural question is, why India produced so many reformers and two of the world's greatest ever in those years?

Society must have needed them. There must have been situations or a culmination of situations which saw society producing these luminaries and accepting them as the guiding lights. The answer to this question could be found in existing social-religious conditions and the material progress of the time. Let's reconstruct both these aspects here.

Social background

In the earlier times, Vedas and Upanishads were the core of socio-religious beliefs. The language of these literature was Sanskrit, a chaste form compared to modern-day Sanskrit to the extent that many historians prefer to call it Vedic Sanskrit or archaic Sanskrit. The population generally spoke their regional languages with enough number of people knowing a few languages from different parts of India. I am not sure when it happened a disconnect had been established between what was written in the Vedas and Upanishads, and what reached to the common people not versed in Sanskrit.

This disconnect had a strong link to how society stratified over the past one thousand years or so. By now, society was clearly divided into four varnas: Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras. It is remarkable to note here is that Brahmanas were originally one of perhaps 16 classes of Vedic priests. But by sixth century before common era, they had developed into a separate caste with their own sub-castes with a claim to the top stratum of society. But their claim was not yet unchallenged. Kshatriyas, who practically owned geography-clamped societies, jostled for supremacy, some of the historians tell us.

|

| Monolithic statue of Gautam Buddha installed in a Hyderabad lake (Pic: Twitter) |

Vish of the Rig Vedic times had classified themselves in several castes but maintained their Varna identity. Shudras had developed from all other Varnas but now had a relegated position for engaging in labour-intensive activities. It is ironical to see that both Kshatriyas and Shudras were in labour-intensive fields, and performed two equally significant basic functions of a society but were seen differently, and occupied almost the extreme ends of the social ladder. Kshatriyas provided protection to society. Shudra fed society, clothed it, gave it shoes, manufactured weapons of protection and served the rest in every possible way to ensure that societal communities continue to flourish.

Now, each Varna was assigned well-defined functions. But unlike the Vedic times, the Varnas were now emphatically based on birth. The two top Varnas enjoyed some privileges. Brahmanas were considered the storekeeper of knowledge and wisdom. This gave them intellectual and psychological superiority over the rest. However, it seems illogical that all from the Brahmana Varna enjoyed the same authority over the rest. There must have been poor among them who had to toil hard to eke their livelihood. But they could not contribute to literature. So, their status is completely unknown. We anyway know only what has survived. The rest is an informed logical guess.

Brahmanas were priests and teachers. They demanded several privileges including those of receiving gifts from the kings, local chieftains and the common people, and also exemption from paying taxes and subjection to punishments for various crimes, if and when they committed. However, they must not have been getting a blanket cover from punishment or were offered gifts without questions or with total devotion as the fate of Chanakya is well-documented.

He lived some 300 years after this phase of socio-religious reforms. Still, he could not claim all that authority which literature of the past generally makes us believe. Again, we know only what has survived. Chanakya was poor despite his father being a well-reputed scholar. He goes to the emperor but was not given gifts that he wanted. He was, in fact, ridiculed. He ended up insulting the king in a fit of rage, and in return, got banished. So, Chanakya originally got neither gift nor exemption from punishment. But some must have got both. This can be compared with today's societal set-up. Not all politicians or professors are equally prestigious or powerful.

Kshatriyas fought and governed claiming taxes, and living off the revenues collected. They were the real power-wielders. But again not all Kshatriyas could have been equally powerful. Obviously, one could be the king and the other the front-line foot-soldier.

|

| (Photo: Twitter) |

The Vaishyas engaged in agriculture, cattle rearing and trade. They employed Shudras in big numbers for their activities. They appear as the principal tax payers. However, along with the two other higher Varnas, they were placed in the class of Dwija -- or twice-born people. This meant that they could hold the investiture ceremony, in which an adolescent male could wear a ceremonial thread across his torso. The three Varnas had different rules for wearing the sacred thread.

Shudras were not allowed to organise the investiture ceremony for themselves. They were supposed to serve the other three Varnas. They along with women of all Varnas were practically denied Vedic education or studies. However, again the literature from later years -- the Chanakya-Chandragupta years -- indicate that this rule must not have been strictly followed or enforced by the ruler-teacher class. For, we see the Nanda dynasty emerge as the most powerful ruling family before the Mauryas came on the scene. The Nandas were said to be from the Shudra Varna. And the Mauryan literature talks about powerful women. The emperor himself was protected by a band of women bodyguards. This would not have been possible if society was so dead against Shudras and women as the surviving literature from the socio-religious upheaval years makes us believe.

But yes, Shudras and women were by now employed as domestic help and lived like slaves. Slaves in India were not comparable to the slaves recorded in the West. Here, their living condition was much more humane making a fourth century Greek ambassador believe and record that India did not practise slavery. Maybe, the Sanskrit word "dasa" is not the correct parallel of "slave" of English.

Shudras were the chief manual labour force in the agricultural field -- some were agricultural slaves. They were craftsmen and craftswomen. They were practically hired for every vocation or business that needed manual labour except warfare. They might have been employed there in support staff as baggage and weapon carriers. Some literature, as historians say, describe them as cruel, greedy and thieving in habit, and some of them were treated as untouchables. Shudras must have made up the biggest chunk of society, and must have felt utterly frustrated with their social, economic and religious positioning in that societal set-up just because of their birth to a particular couple branded as belonging to a particular Varna.

There must have been yearning for luxury and respect among them. The societal set-up was such that the higher the Varna the more privileges and purity one could claim. For the same offence, Shudras would get severer punishment compared to Brahmanas.

Naturally, Varna-divided society would have generated tensions. There are no means to ascertain the reactions from Vaishyas and Shudras. But Kshatriyas, who were the royalty, recorded their reaction against the ritualistic domination of Brahmanas. They appear to have led a sort of protest movement to demolish the principle of importance attached to birth in the Varna system. Their protest saw Brahmanas as targets, not violent but ideological. It is no mere coincidence that the two of the greatest socio-religious leaders were Kshatriyas -- Vardhman and Gautam.

Material base

This is considered as a bigger factor contributing to the rise of socio-religious reforms in the sixth century before common era. It was the time of the introduction of a new agricultural economy in the middle and lower Gangetic plains. Introduction of iron technology to agriculture heralded the transformation.

These areas -- from Bihar-Bengal to eastern Uttar Pradesh -- were thickly forested in earlier times. The Aryan people cleared the forests for agriculture, as literature suggests. In the middle Gangetic plains, large scale habitations emerged around 600 BCE, as a result. The use of iron implements made forest clearing, farming and large-scale settlements easier. Agriculture-based economy got a new fillip with iron ploughshare, which required the use of bullocks. The supply of bullocks needed a flourishing animal husbandry as vocation.

|

| It was not that only Magadh rose to power. Kingh Kharvel invaded Magadh and defeated its king, and brought back Jain's statue to Kalinga (Photo: Twitter) |

A whole new economic equation came into place. This was in a sharp contrast to the Vedic practice of indiscriminate sacrificing of cattle -- a necessity of the time to maintain a population balance in a society that thrived on milk and other cattle products, and used the same for transportation. The sacrifice of cattle in religious ceremonies meant that demand for bullocks could not be met. This came in the way of the new phase of agricultural revolution. The cattle wealth had slowly declined, the historians tell us. They also tell us that some communities, particularly those living on the southern fringes of the emerging Magadh empire, killed cattle for food. New agricultural revolution challenged their food habit by making availability of food easier than before, and also needed them to change their food habits so that there was no short-supply of cattle needed for the farms.

If the new agrarian economy had to be stable, this indiscriminate killing of cattle with religious sanction needed to be stopped. A new guiding religious belief had to emerge to sustain the civil living based on new agricultural revolution.

In other words, the time had come for an idea backed by socio-religious philosophy that could preach absolute non-violence in an intellectually and spiritually glamourised fashion.

The period saw the rise of a large number of cities in the middle Gangetic plains. We all know a city organically grows only when there is abundant supply of food. If food supply is not assured, hunting, gathering or farming remains the primary vocation. City-life is a tertiary scale of socio-economy. These new cities needed and had many artisans and traders, who began to use coins for the first time on regular basis for economic exchange. The earlier barter economy exchange model could not support the growth. The earliest coins to survive belong to the fifth century before common era, and are called the punch-marked coins.

The use of coins naturally facilitated trade and commerce, which added to the importance of Vaishyas. But in the Brahmanical order, they did not get much importance. So, they looked for an order, which would improve their social position. This is why Vaishyas extended generous support to both Mahavira and Buddha.

Further, Jainism and Buddhism, in their initial stages, did not attach any importance to the existing Varna system. Secondly, they preached the gospel of non-violence, which would put an end to wars between different kingdoms and consequently promote trade and commerce. Third, the Brahmanical law books, called Dharmashastras, decried lending money on interest. A person who lived on interest was condemned by them. Therefore, Vaishyas were not held in esteem and were eager to improve their social status.

On the other hand, there was a also strong reaction against various forms of private property. The new forms of property created social inequalities, and caused misery and suffering to the masses. So, the common people yearned for a more harmonious life and society. The ascetic ideal was one of the ideas espoused by the Vedas. A section of society now must have wanted to adopt this ideal, which was dispensed with the new forms of property and the new style of life.

Both Jainism and Buddhism preferred simple puritan ascetic living. The Jain and Buddhist monks were asked to forego the good things of life. They were not allowed to touch gold and silver. They were to accept only as much from their patrons as was sufficient to keep their body and psyche in harmony. The people, therefore, identified themselves such monks and supported the religious reactions against the Vedic religious practices.

Also, since both Vardhman and Gautam came from ruling Kshatriya families, they commanded authority over both the priestly class and the common populace. Their ideas were patiently listened to, and adopted as far as possible. Since they came from Kshatriya Varna, the Brahmanas could not denounce them with arguments that they were not versed in the Vedas. This logic would not have any weight in society. Brahmanas were the interpreters of the Vedic religion and system, and Kshatriyas were enforcer of the order.

Now, Kshatriyas took up the task to modify the social order and bring about a socio-religious reform. This went a long way in giving Jainism and Buddhism credibility as the royal warrior class produced teachers who preached peace and denounced the malpractices of the Vedas. This explains why unlike Christianity, where a non-violent preacher Christ needed a warring emperor to take off 300 years later, Jainism and Buddhism got royal support almost since their beginning, and none used the new religious ideas to launch a war on the other kingdom. Both kingdoms could be adopting the new ideas. And it also explains why Mauryan emperor Ashoka took the task of spreading Buddhism after renouncing warfare.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Vardhaman Mahavira: An introduction to Jainism

|

| Vardhaman Mahavir temple, Madurai/Twitter |

Vardhaman Mahavira was born in 540 BC in Kundagram near Vaishali. At the age of 42, he attained the state called Nirvana (cessation). The jnaan that attained is called kaivalya (omniscience) – the realisation of one’s self. He was acclaimed as a tirthankara (forth finder), a kaivlin (the supreme omniscient), jina (conqueror) and arhant (the blessed one). He was henceforth called Mahavira, the great hero.

At the age of 72, Mahavira died in Rajgir in 468 BC at a place called Pavapuri. Mahavira recognised the teachings of 23 previous tirthankaras, about whom nothing is practically known. Many historians believe that only the last tirthankara, Mahavira, was a historical personage.

However, most of them are known by their names and symbols. Mahavira is regarded as the historical founder of Jainism. Rishabhadeva or Rishabha was the first Jain tirthankara. The word, Rishabha, means a bull, hence some scholars link him to the bull worship of Mohenjodaro.

Mahavira told his followers that their deeds should be based on Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Action. These are called the tri-ratnas or three jewels of Jainism.

Right Faith is the belief in what one knows.

Right Knowledge is the knowledge of the Jain creed.

Right Action is the practice of five vows of Jainism, namely, non-injury to living beings (ahimsa), truth (satya), non-stealing (asteya), not to own property (aparigrah) and practising chastity (brahmacharya).

The first four vows were laid down by Parshwa and the fifth one was added by Mahavira, who also asked his followers to abandon clothes and go about naked.

Jainism emphasises on reality, which it describes as anekatva or plurality or multi-sidedness. It is beyond the finite minds to know all aspects of a thing. All our judgments are thus necessarily relative. There is no certainty in any knowledge, and hence, syadvad (the perhaps doctrine) is the wisest course to follow. To every proposition, the correct reply is syad, i.e. perhaps. There can be no absolute judgment on any issue.

Jainism represents the universe as something functioning according to an eternal law, continuously passing through a series of cosmic waves of progress and decline.

Jainism proposes the principle of duality of jiva (eternal being/energy/some scholars have called it soul) and ajiva (eternal element) as applicable everywhere. The jiva acts and is affected by its actions, it is a knowing self; the ajiva is atomic and unconscious. Every object is an agglomeration of ajiva with at least one jiva enmeshed in it.

Everything material, even inanimate objects, has at least one jiva. Plants and trees have two jivas. For that specific reason, a fruit should preferably fall from the tree before it could be eaten. It must not be plucked by the followers of Jainism. Animals have three or more jivas. Jains are permitted to eat things with two jivas. To eat things with three jivas is forbidden. It is considered a breach of the vow of ahimsa.

Mahavira preached in Magadhi, the language spoken by the common people of Magadh. Initially, his teachings were confined to the Ganga Valley regions but in the later centuries, Jainism moved to western parts, and also northern India (Rajasthan), and to the south in Karnataka.

Jainism was popular among the trading community members, who became its champions and spread it to far flung areas.

Jain teachings were at first presented in an oral tradition. But in the third century BC, at a council convened in Patliputra, it was collected and recorded. The final version was edited in the fifth century at Vallabhi. At the time of the council, the jains were divided into two sects – Svetambara and Digambara. The digambaras refused to recognise the rearranged and edited version of the 12 Angas as authentic. The digambaras were the ones who did not wear clothes. Svetambaras are those who wore white clothes.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Tuesday, May 3, 2022

Buddhism: Institution of Sangha

The Sangha was the religious order of the Buddhists. It was a well-organised and powerful institution, which popularised Buddhism. Membership was open to all persons irrespective of caste. There was age criterion for eligibility. The inductee must have completed the age of 15 at the time of becoming a member of the Buddhist Sangha. Interestingly, many millennia later, legislators thought 15 is the right age for giving consent.

Besides,

the Buddhist Sangha would not accord membership to criminals unless reformed,

lepers (controlling infection through medication was not known or common back

then), slaves (their status in those times in India remains a subject of

discussion among historians), persons suffering from an infectious disease, and

an indebted person (who needed to pay off her debt before earning eligibility).

The Buddha

was not initially inclined to admit women into the Sangha fearing that a

gender-mix might make it difficult for the Sangha to maintain the requisite

discipline. His chief disciple, Ananda, and foster mother, Mahaprajapati

Gautami, argued for their entry into the Sangha.

The Buddha

agreed but it is said in some stories that he warned Ananda that the decision

would weaken the institution of the Sangha and cut short its life by 500 years

which would have served society for a thousand years otherwise. The Sangha

weakened over the following centuries particularly in the post-Ashoka era but

picked up strength during the Kanishka times.

The members of the Sangha were monks and followed a bureaucratic hierarchy to manage the affairs of the institution. The monks had to ceremonially shave their head and wear yellow or saffron robes upon admission into the Sangha.

Monks were

expected to go on a daily round in order to preach Buddhism and seek alms to

feed themselves. During the four months of rainy season, they stayed at one

place, usually fixed, and meditated on the questions of the contemporary

society and find answers from the tenets of Buddhism. This was called the

retreat or Vasa.

The Sangha

also promoted education among people. Unlike Brahmanism, people of different

orders of society got access to education under the Buddhist Sangha. Naturally,

the non-Brahmins got educated and the formal education reached wider sections

of society, a departure from the history of past few centuries.

The Sangha

was governed on democratic principles. It was empowered to enforce discipline

among its members. There was a code of conduct for the monks and nuns. But

differences were cropping up in the Sangha even during the time of the Buddha.

Paul Carus,

the celebrated author of the “Gospel of Buddha”, says the Buddha, on the advice

of Magadh king Bimbisar who was planning retirement, marked two days in every

fortnight for community preaching by a monk ordained in Buddhism. He fixed the

eighth and 14-15th day of every fortnight – a model Bimbisar had suggested on

the lines of the practice of some Brahmanical sect of Rajgriha, his capital.

People

started flocking to such community preaching events. But soon they complained

that the monks who were supposed to elucidate Buddhism. A dispute arose. To

settle the dispute, the Buddha provided for Pratimoksha (pardon by the Sangha

after self-confession of indiscipline or violation of the Sangha rules by a

monk). This was to be done on the same two days of the fortnight. This meeting

and the process was called Uposatha and was to be held in public.

The monk

who violated the Buddhist code had to confess upon being asked by the senior

monk at the Uposatha. Others were to remain silent. The question was to be

asked three times. If a violator remained silent three times, she/he would be

considered guilty of perjury, which was an obstacle in attaining nirvana –

freedom from the cycle of suffering.

At another place, Carus has shown that the Buddha walked out of a Sangha event as the rival monks would not listen to reason. After some time when his disciples insisted upon finding a solution, the Buddha addressed both the sides, first separately and then jointly. He had asked his disciples not to discriminate against one group or the other for their preference for one or abhorrence of the other.

In the joint session, the Buddha told them the story of a Koshal

king Deerghiti, his rival Kashi king Brahmadutta, and Deerghiti’s son Deerghayu

who ended the bitterness between the two royal families. Here, the Buddha

enunciated that hate could only be conquered by hatelessness – something that

became popular after the Bible’s narration of ‘an eye for an eye will make the

whole world blind’.

Thus, the

members of Sangha – both monks and nuns – had to follow their respective codes

of conduct. They were bound to obey the code if they were to stay within the

Sangha. The Sangha had the power to punish any of the erring members.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

Buddhism: Teachings of the Buddha

The basic

teachings of the Buddha are contained in:

-

Four

Satyas (noble truths)

-

Eight

paths (Ashtangika Marga)

The four

noble truths are:

1. The world is full of sufferings.

2. All sufferings have a cause. Desire,

ignorance and attachment are the causes of these sufferings.

3. A suffering could be removed by

destroying its cause.

4. One must know the right path to end

the sufferings. This path is eight-fold or the Ashtangika Marg.

The

eight-fold path is enunciated as follows:

1. Right View/Observation: Finding the

right view through observation is the first of the paths. This is required to

understand that the world is filled with sorrow emerging from desires. Ending

the desire will lead to liberation of the self.

2. Right Aim/Determination: It refers

to having the determination for the right aim, which is to seek to avoid

enjoyment of the senses and luxury. It aims to love the humanity and augment

the happiness of others.

3. Right Speech: It emphasises the

endeavour to speak truth always.

4. Right Action: This is interpreted as

unselfish deeds or action.

5. Right Livelihood: This path

instructs a follower to live his or her life by honest means. This does not

take an extreme position. For example, it allows profit-making by business

people but without subjecting somebody to sufferings.

6. Right Exercise: This means making

the right efforts, interpreted as the proper way to control one’s senses so as

to prevent bad or detrimental thoughts. It elucidates that one can destroy

desires and attachments through right mental exercises.

7. Right Memory/Mindfulness: It

recognises that there are evil worldly affairs which trigger desires and

attachments. This path calls for understanding the idea that the body is

impermanent, and that meditation is the means for removal of the worldly evils.

8. Right Meditation/Concentration:

Observation of the right meditation will lead to inner peace. The right

meditation will unravel the real truth.

Buddhism

puts great emphasis on the law of karma (action). This means that the present

is determined by one’s past actions. Everyone is the maker of one’s own

destiny. The condition of a person in this life or the next life depends on

one’s own actions. Humans are born again and again to reap the fruits of their

karma. If an individual has no sins or desires, she or he is not born again.

The

doctrine of karma is an essential part of the Buddhist tenet. The Buddha

preached nirvana, described as the ultimate goal of a human life. One can

attain nirvana by the process of elimination of desires. The Buddha laid

emphasis the moral life of an individual to complete this process.

Buddhism is

what could be termed a secular religion for the Buddha neither accepted nor

rejected the existence of god. He did not consider the god question as

significant enough to discuss. He was more concerned about the individual and

one’s action than deliberating the question of god. The Buddha did not believe

in the existence of soul either. It is unique in being a soul-less religion.

This means there is no heaven in Buddhism.

The Buddha

emphasised on the spirit of love, which he said could be harboured for all

living beings by following the path of ahimsa, non-violence. The principle of

ahimsa was underscored and emphasised in Buddhism but not as much as in

Jainism. The Buddha prescribed that an individual should pursue the middle-path

shunning the extremes of severe asceticism and luxurious life.

The

teachings of the Buddha posed a serious challenge to the existing Brahmanical

ideas in the following ways:

1. The Buddha’s liberal and democratic

approach towards life quickly attracted people from all sections of society.

His disregard for the caste system and the supremacy of the Brahmins through

the law of karma was welcomed by the people who were given lower social strata

in the pecking order. People were admitted to the Buddhist order without the

consideration of caste and, later, gender.

2. Salvation of an individual, Buddhism

declared, depended on one’s good deeds not the birth in a particular community.

This meant that there was no need for a priest or spiritual middle-man to

achieve nirvana.

3. The Buddha also rejected the supreme

authority of the Vedas by condemning the practice of animal sacrifice. The

Buddha said neither a sacrifice to gods could wash away a sin nor could any

prayer of any priest do any good to a sinner.

With these

influences, Buddhism in a very short period emerged as an organised religion

and the Buddha’s teachings were codified forming the Buddhist cannon, the

collection of his teachings. The Buddhist cannon can be divided into three

sections:

1. Sutta Pitaka: It consists of five

Nikayas (bodies) of religious discourses and sayings of the Buddha. The fifth

of the Nikayas contains the Jatakakathas (the tales of the births).

2. Vinaya Pitaka: It contains the rules

for monastic discipline.

3. Abhidhamma Pitaka: It contains the

philosophical ideas of the teachings of the Buddha. It is written in the form

of questions and answers.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.

A sapien. Friend. Accidental journalist. Believe God is the greatest creation. Convinced that words, stories built human civilisation with the help of communication technology. Live in a metro with a heart of small town. Dreamer. Lover of humans, other natural things. Poetry. Philosophy. Lazy. Leisure. Beholding eyes for beauty. Life is a sentence that ends at a full stop.